When the sun rises in this remote region of northern Kenya at 6 a.m., it is a new dawn for Missionary Sr. Lilly Manavalan. Her day starts with a trek for over an hour across a deep valley to reach the streets where she can find vulnerable children living with HIV.

On a normal day, she takes two children who have lost their parents and are themselves infected with the virus to St. Clare Girls' Centre in Nchiru, Kenya, where she gives them a home with love, and a future with promise while offering them a new beginning in Christ.

"This is my passion and I really like being with the poor people," said the Franciscan Clarist nun. "I feel very happy and satisfied when I assist the poor, especially those suffering from HIV/AIDS."

Manavalan, who is from Kerala state on the southwestern Malabar Coast of India, is a nurse at St. Clare Centre. She has passion and resilience to help impoverished people, many living with HIV. She developed the desire to work in northern Kenya after her colleague informed her that many people in this part of the world had no knowledge about HIV, AIDS or sexual health, she said.

The Northeastern Africa nation's 2014 HIV and AIDS Stigma and Discrimination Index shows that 98 percent of people living with HIV in this region do not have close ties with their families. The report also indicates that 83 percent of the residents believe that people who are HIV positive are punished by God for bad behavior, while 72 percent believe that the virus is spread by sex workers.

Manavalan came to Samburu in 2009 specifically to help those suffering from bias related to HIV/AIDS.

"I have committed to address stigma and discrimination," said Manavalan. "I realized that many do not know how HIV is spread and do not believe they are at risk. Others don't want to associate with anyone living with the virus."

Residents of the Samburu tribe — usually living in groups of five to 10 families, believe that HIV does not belong to them but to outside communities. The locals consider people with HIV/AIDS to be cursed, sinners and among the walking dead.

Recently, a group of brightly dressed men and women on the dusty streets were heard using harsh voices, distancing themselves from those living with the virus.

"HIV is not our disease, it's the disease of the urban people," said John Lepariyo, 60, in a low, deep voice. "People who suffer from such kind of disease are considered cursed and we try to separate them from other members of the community because we fear they might spread the virus."

The Samburu people are semi-nomadic pastoralists, whose lives center on their cattle, goats, sheep and camels. The people of this region are strongly rooted in their culture, norms, beliefs and values. As a result, some infected persons, especially children, have been abandoned by their families and communities on the streets and left to die. Others fear going for medication at nearby health facilities due to discrimination.

Manavalan said she offers the children a nutritious diet to boost their immune systems, education and necessary medications.

"We give them the best accommodation, medicine and free treatment," said Manavalan. "We also do counseling and teach these children catechism. We want them to know that God belongs to all of us despite our status."

The approach has changed the lives of many children who have been falsely accused of spreading the deadly virus to anyone who attempts to assist them, she said.

Sixteen-year-old Joyce (not real her name) is one of the girls who was rescued by Manavalan from the streets. She was made an outcast in her village after elders found out that she was HIV positive. She was expelled from the village for fear she would infect others with the virus.

Depressed and having nowhere to go, she sought refuge on the streets before she was rescued and taken to the center run by the sisters from India. The center serves more than 500 children.

"I felt so low, so heartbroken and out of this world," said Joyce, who was rescued from Wamba, a village in the Samburu region. "My mother and everyone left me because I was HIV positive. My friend started telling my story to my classmates and I started feeling lonely. People stopped mingling with me."

Today, three years after Joyce was rescued, the memories of her time in the village and on the streets are still fresh in her mind. However, thanks to Manavalan, Joyce is happy and healthy and doing very well at school.

"I now feel so loved and cared for," she said. "When I finish high school, I will go to college then come back to work at the center and help children who are living with HIV. I advise those with the same condition to accept their status and just be themselves."

Martha (not her real name) was rescued five years ago by Manavalan after being expelled from her village and left to die on the street.

"I was very malnourished when I was brought to this center," said the 14-year-old from Archers Post, a small town in northwestern Kenya. "I was waiting to die because I had lost hope in life. Sister Lilly took me to the hospital and I received medications and treatment. I'm now happy and I want to become a nurse when I finish high school."

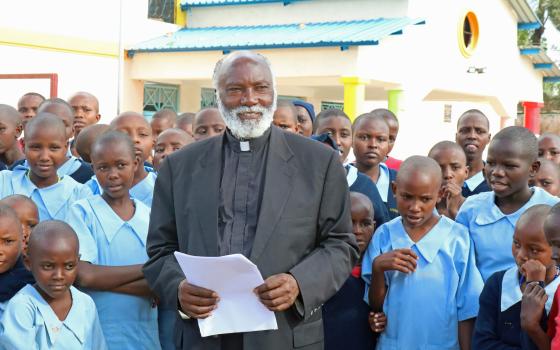

Fr. Francis Riwa, the founder of the rescue center, heads both the center and the clinic and teams with Manavalan to rescue the children on the streets. Two other Franciscan Clarist sisters assist them at the center and the clinic.

Riwa commended the nuns for providing health services, counseling and psychological support, as well as care and assistance for those living with HIV/AIDS.

"I want to thank the sisters because they have shown these children the true love of Jesus Christ," said Riwa, 62, who also owns and operates schools and other homes in the region. "They have embraced and counseled these children. Many have recovered from emotional wounds and have purpose for living."

The priest, who is also a doctor, said there are lots of myths and misconceptions in the region about how one can get HIV. He encouraged sisters to continue educating the communities about the virus.

"I have told people around here that the virus can only be passed on from one person to another through breast milk, blood, semen, anal mucous and vaginal fluid," he said. "The majority of people believe that one can get HIV from touching someone, hugging them or shaking their hand."

Local officials contacted by Global Sisters Report had no comment about the troubles of those living with HIV/AIDS in Samburu. Elders said it was impossible for local officials to go against the community's culture and beliefs even if they wished to speak truthfully about the virus.

"These leaders were born here and they know our culture. They are very aware that we fear those people living with HIV/AIDS," said Lepariyo, an elder.

Meanwhile, Manavalan vowed to continue rescuing more children and educating the community.

"I want to save more lives of vulnerable children from the streets," she said. "My desire is to see the community accept people living with HIV."

[Doreen Ajiambo is the Africa/Middle East correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Nairobi, Kenya.]