Two-year-old Rebecca Rubio's collarbone no longer protrudes as noticeably as it did two years ago.

She still weighs only 20 pounds and, as evidenced by her skinny arms and small frame, could stand to gain more weight. Doctors have told her mother she should already weigh 26 pounds. After a recent cold, she once again was classified as malnourished but has since recovered.

But Rebecca's situation could be much worse.

A recent New York Times investigation confirmed long-held but until recently unproven fears that hundreds of Venezuelan children like her have essentially starved to death because of the country's economic crisis. Rebecca's mom, Yudelsi Avila, has maintained her daughter's weight largely thanks to the work of two sisters and Catholic organizations like Caritas Internationalis.

"If this clinic wouldn't have existed, I have no idea what would have happened, because it's thanks to the sisters and Caritas that my daughter has changed," Avila said as her daughter sat on her lap, eating a small cup of oatmeal provided by Sr. Yexci Moreno.

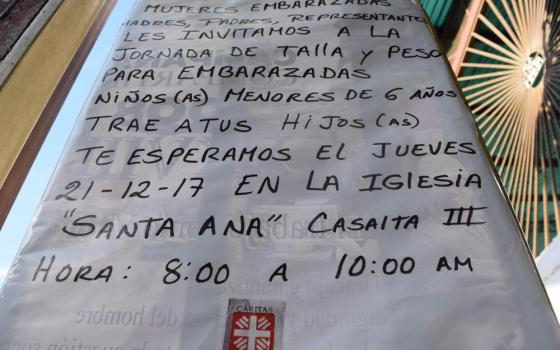

From September 2016 to July 2017, Moreno and Sr. Teresa Gomez of the Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception of Castres congregation hosted nutrition clinics at their preschool in Caracas' working-class neighborhood of Propatria. As they prepare for the school year to begin, they've begun the clinics again.

Volunteers weigh and measure children under 5 years old to detect signs of malnutrition. At the first clinic after the recess on Dec. 21, 15 of the 25 children who attended were malnourished.

"This year in the community, the situation has only gotten worse in terms of food supply, medicine supply, and quality of life," Moreno said. "We have people who show up to the school asking for food, and then they faint."

In the fourth year of the worst economic crisis in its history, once well-off Venezuela continues to experience food and medicine shortages. According to OPEC figures, the country relies on oil for up to 95 percent of its export revenue, and as oil prices plummeted in recent years, the government has found itself without the cash to import essential products. The situation has been further complicated by widespread corruption and mismanagement.

As economists and experts continue to present figures that reveal the depth of Venezuela's economic crisis, the country's hardships can also be measured through the stories of low-income neighborhoods like this one.

Here, parents have struggled to afford enough food for their families, often skipping meals themselves to feed their children. New mothers unable to breastfeed and faced with shortages of baby formula agonize over whether they should feed their newborn babies whole milk, rice water or nothing at all. Parents worry that a simple scraped knee could become infected and lead to serious complications should they not find antibiotics.

Even though the central bank has stopped releasing official figures, in 2017, inflation was believed to have reached 2,000 percent. The constant increase in prices has eaten away at salaries, and now, one day's minimum wage won't buy a single egg.

Shortages of basic foods and medicines in pharmacies and supermarkets further complicate daily life for lower- and middle-income Venezuelans.

Humanitarian workers visiting the country have described the situation as a developing humanitarian crisis.

"This is a really bad one, a country in real crisis," said one aid worker who has assessed humanitarian emergencies throughout the world and did not want be identified either by name, agency or by nationality because of the worker's ongoing work in Venezuela.

Dr. Susana Raffalli, who has overseen the Caritas nutrition clinics since September, calls the situation an "emergency" because of its rapid deterioration.

"Malnutrition among children has become more and more severe," she said.

Initial figures from the clinics showed 54 percent of children who attended were malnourished, and Raffalli said those numbers continue to surge: They have observed rates of severe malnutrition nearly double since the clinics began, from 8 to 15 percent, classifying the situation as a humanitarian emergency.

The sisters have also observed that trend with the more than 100 children who attend their preschool. When classes resume this month, they expect many of the children will return skinnier than when they left.

During the school year, which ended in October, the sisters provide breakfast and lunch to each student. But when classes aren't in session, the parents must provide those meals.

"We always will say, 'Wow, that kid came back a lot thinner,' and the parents will say that it's because they're growing," said Carmen Marquez, who has taught at the school for several years. "But it's because they haven't been eating properly."

Marquez will sometimes slip some of the children who appear thin some extra food from her own lunchbox, despite struggling to get by herself: She stopped taking her 1-year-old son to the pediatrician to save money to buy food. He hasn't taken his asthma medication in months because she can't find it in pharmacies.

The sisters try to help their community however they can. Along with the weekly clinics with Caritas, they deliver food to families in need with the local Catholic organization CESAP. They host frequent soup kitchens at the school. They also hold yard sales, selling donated clothes at cheap prices.

The sisters also helped one local family several times last year, organizing fundraisers and collecting donations. In 2017, Mariana Rodriguez helped her brother, who was shot in the leg during an attempted robbery; her daughter, who required surgery when her pacemaker slipped; and her husband, who cut off his index finger during a woodcutting accident.

As the family matriarch, she also makes sure all of her grandchildren are eating properly. Doctors had recently warned her daughter-in-law to stop feeding her 7-month-old son whole milk as a substitute for formula or breast milk.

"The sisters organized a Sunday fundraiser, and without them, I don't know how we would have made it this year," she said.

But the help of the sisters and organizations like Caritas and CESAP only reaches a small percentage of those in need. The Caritas clinics, which also provide nutritional supplements and will soon provide bags of food, will expand from four to six Venezuelan states in 2018.

Raffalli estimates her clinics assist less than 5 percent of children who could face malnutrition.

"This requires action by the state," she said. "We as civil society could maybe reach 10 percent, but that's it."

So far, the Venezuelan government has turned down international aid, denying that a humanitarian crisis exists. Some say officials worry that admission could invite not only aid, but foreign intervention, as well.

The Venezuelan Consulate in New York did not respond to requests for comment.

Because the government will not deal with the situation, the aid worker working in Venezuela said it will be up to civil society and nongovernmental actors like Caritas and the Catholic Church "to guide the country out of the crisis, and the church will have a large role to play in this."

"The Catholic Church is a voice, an important voice, in filling this void," the worker said.

The worker, who observed the nutrition clinics, noticed that Caritas volunteers are "under great stress and pressure," trying to locate items "here and there" before shortages occur. That makes their work "tactical but also reactive," the worker said. "They are constantly on the search for food."

Until the situation improves or aid is permitted, more children will likely die from malnutrition complications. According to the New York Times, at least 400 have died already. Hospitals have started turning starving children away.

The crisis will likely worsen in 2018, with the International Monetary Fund projecting inflation to reach 2,300 percent annually. Mothers like Yudelsi Avila will continue to struggle to feed their families while also feeding themselves.

Although the help of Caritas and the sisters has helped Rebecca maintain a healthy weight, Avila has neglected her own nutrition. A few months ago, she learned she had become anemic.

"We just don't eat like we used to," she said.

[Cody Weddle is a freelance journalist based in Caracas, Venezuela. Follow him on Twitter: @coweddle. Chris Herlinger, international correspondent for GSR, contributed to this story from New York.]