Experienced as nurses, nuns were in high demand during the Civil War, bringing domestic comfort to battlefield soldiers and starting to thaw an icy national reception to immigrant Catholics. In this engraving by artist Winslow Homer published Sept. 6, 1862, in Harper's Weekly, a nun offering a bedridden man a rosary figures prominently. (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

(GSR logo/Toni-Ann Ortiz)

What a long, strange trip it's been.

Today, sisters all over the United States work with immigrants, teaching them English, advocating for humane treatment of workers who toil in factories and fields, defending the rights of undocumented families at the U.S. border fleeing hardship in Central America and elsewhere. In those roles, they attract relatively little notice. After all, isn't this what sisters are expected to do?

But it wasn't always this way. Once, nuns, now well integrated into the fabric of American life, were seen as foreign invaders.

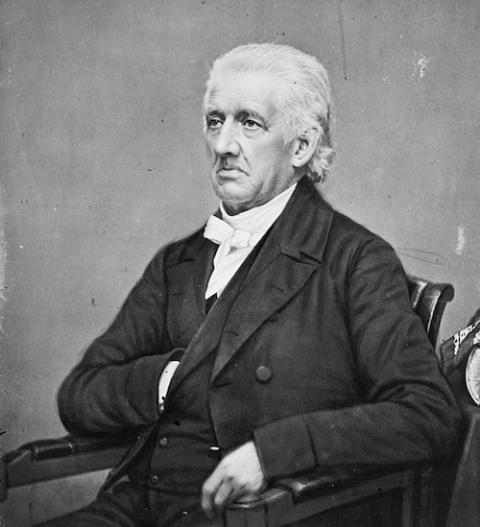

In the 19th century, immigrant nuns were viewed with profound hostility by members of the Protestant establishment. Ironically, that included a few famed abolitionists, such as Presbyterian pastor and American Temperance Society co-founder Lyman Beecher. At best, suggested some, the women were dupes of a clever group of priests and bishops determined to set up alternative (and competitive) systems of education and faith. At worst, they were suspected of owing allegiance to a foreign power headed by the covert figure of the pope.

The story of Catholic sisters was that of the rise of American Catholicism writ large: immigrants confronted with suspicion and resentment who ultimately succeeded in not only integrating themselves into American culture but leaving an indelible mark on it.

Pictured between 1855 and 1865, Presbyterian pastor Lyman Beecher, scion of the famed Beecher family, was known for his fiery oratory about the evils of slavery and liquor. He was also, in common with many other Protestants of that time, anti-Catholic. (Brady-Handy photograph collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

A hostile beginning

But in the early 19th century, the signs that sisters, and Catholics themselves, would become a part of the fabric of national life didn't seem particularly auspicious, suggested scholars of the period.

"From the burning of Boston's Charlestown [Ursuline] Convent in 1834 and the rise of the single-issue, anti-immigrant Know Nothing party in the 1850s (an organization that, for a brief moment, controlled dozens of congressional seats and enjoyed extensive influence within the political anti-slavery coalition) — to the No Irish Need Apply signs of the 1890s — immigrant Catholics faced the brunt of Protestant America's rage," wrote historian Josh Zeitz in a 2015 Politico analysis titled "When America hated Catholics."

While there was some suspicion of practitioners in the American colonies, including among revolutionary groups like the Sons of Liberty, most Catholics of that era were established landowners who shared a common Anglo culture, said Kara French, a professor of history at Salisbury University in Maryland.

"A lot of the efforts to contain Catholicism have to do with immigrants coming to the United States into what is a very hostile culture and trying to maintain identities in communities that sometimes want them dead," said Hampton University (Virginia) assistant professor of history Michael Davis, noting that Catholic churches built in the 1830s and '40s in large cities resembled fortresses.

There is evidence that some sisters of the time were concerned about the danger that they might face when starting new missions on potentially hostile territory.

Protestant pushback

Post-revolutionary America saw significant growth in Catholic institutions, including the founding of religious orders for women (like Elizabeth Ann Seton's Sisters of Charity in 1809), said French. By the 1830s, priests and nuns were becoming more visible while immigration from Ireland, Germany and Eastern Europe was taking off, she said.

To suspicious Protestants, women religious were obvious stand-ins for Catholicism, said Margaret S. Thompson, an associate professor of history and political science at Syracuse University (though, as Thompson pointed out, antagonism towards the Catholic Church has deep roots that date back at least to the time of the Protestant Reformation). "They are highly visible, there are more of them than priests, they wear habits, they look different, which is highly suspicious, and they don't marry. They give women options outside of marriage. So, in that sense, they are dangerous."

Protestant distrust of nuns — as well as of priests and bishops, who were assumed to be pulling the strings of these "dupes" — found expression in a string of lurid novels. They purported to depict the tragic fate of innocent young women lured into the clutches of nuns and priests, only to stumble into a cesspool of iniquity.

The most famous of the tales, which were popular from the 1830s to 1860s, was The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk.

The real Monk was a Canadian woman who said she had entered a convent in which sisters were forced to have sex with priests at the local seminary, the resulting babies aborted and buried.

From left: Kara French, professor of history at Salisbury University in Maryland (Courtesy of Kara French); Margaret S. Thompson, associate professor of history and political science at Syracuse University (Courtesy of Margaret S. Thompson); and Brian Regal, history of science professor at Kean University in Union, New Jersey (Courtesy of Brian Regal/Lisa Nocks)

While she apparently never lived in a convent (though she is said to have spent some time in an asylum as a child), and her claims were both challenged and disproven at the time, the book itself was a bestseller, only second in that era to Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, said Brian Regal, a professor of the history of science at Kean University in Union, New Jersey, who made a study of such books for his master's thesis.

A reliable source of income for their publishers, the books (Regal estimates there were about half a dozen) always have the same theme, he said. "It's the trope of the innocent young Protestant girl who gets enthralled by the Catholic Church and enters a convent, only to be exposed to the horrors of foppish religion. Terrible things go on behind closed doors."

In these tomes, once the young woman escapes, she finds herself in a circle of Protestant clergy "who have dark visions of what the church is about. Then they write a book, go on tour, and a mass media frenzy begins."

The nun sagas, said Thompson, "draw on a whole anti-convent tradition" that can be traced back to the Reformation. And the idea that sisters were unmarried was also troubling to many 19th-century American Protestants, who believed that women's greatest fulfillment was being a wife and mother, she said.

Advertisement

Into epidemics, disasters and the Wild West

But as nuns began to found orders and missions across America, local communities were able to sort out myth from reality. Communities reeling from epidemics and other disasters recognized the sisters' willingness to take on the difficult and often dangerous work of caring for the sick, sheltering orphans, and helping the poor.

When Mother St. John Fournier, who helped lay the American foundation of the Sisters of St. Joseph, moved with a small team of nuns from St. Louis to Philadelphia in 1847, she was aware of the nativist riots that had wracked the Pennsylvania city and did it with great hesitation, said Ryan Murphy, who teaches sociology at Chestnut Hill College there. The sisters were "well aware of the tensions and difficulties Catholics were experiencing," said Murphy.

But the sisters were quick to establish themselves as educators, open a hospital, and care for orphans. "Over the next decades, anti-Catholic sentiment began to fade," he said.

When the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, founded in 1840s Quebec, arrived in Portland, Oregon, in 1859, the area literally was the "wild west," said Sr. Carol Higgins. A longtime educator, Higgins now serves on the provincial leadership team for her community. "There were very few Catholics, and our sisters were predominantly French, not English-speaking. There are stories from the very beginning about our nuns being viewed with suspicion, people seeing them and crossing the street, or cursing [and] spitting at them."

Sr. Carol Higgins, of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary is an educator and part of the leadership team with a longstanding interest in the history of her order. She is pictured at the Marylhurst Convent in Oregon during a provincial chapter. (Courtesy of Carol Higgins)

That antagonistic attitude changed fairly quickly, she added, once the sisters began to take care of locals afflicted by smallpox and opened an orphanage in the Portland area.

The Civil War, during which nuns from a dozen orders were the only trained nurses, showed Americans of all faiths that sisters were willing to serve anyone, regardless of faith affiliation.

Thompson noted that Congress authorized a monument in the 1920s to battlefield nuns, though the Ku Klux Klan was surging in popularity at the time.

"I am not of your Church, and have always been taught to believe it to be nothing but evil," an imprisoned Union soldier wrote to the Sisters of Mercy's mother superior in an 1864 letter. "However, actions speak louder than words, and I am free to admit, that if Christianity does exist on the earth, it has some of its closest followers among the Ladies of your Order," quoted Nic Rowan in a 2019 commentary about battlefield nuns in the Wall Street Journal.

After the Civil War, sisters, who had established religious communities and offshoots across the United States, were instrumental in creating institutions, like hospitals. It didn't take long for them to become central to American society.

It's hard to accuse a ministering angel on a battlefield or a hospital nurse of sinister motives.

"One of the reasons that the sisters were not targeted as immigrants is because the fears often associated with immigrants from the late 19th century — fears of dependency, economic dependency, disease, moral degeneracy, social disorder, you know, things that people were worried immigrants were bringing to the United States — can't be pinned on sisters," said Tom Rzeznik, an historian of American religion at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey.

Thomas Rzeznik, a historian of American religion at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey, visits the Sisters of Mercy Heritage Center in Belmont, North Carolina. (Courtesy of Thomas Rzeznik)

Biological sisters who immigrated from Italy as children, Maria Rosa and Maria Maddalena Segale were inspired to become nuns in part by the work of the Civil War nurses they had heard about. Maria Rosa became Sister Blandina, and Maria Maddalena, Sister Justina when they joined the Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati in the late 1860s.

Missionaries to the Southwest before returning to Ohio, (Sister Blandina is famous for her encounter with Billy the Kid and other proponents of frontier justice), "they were always educating the public who had misgivings about sisters and Catholics," said Mary Beth Fraser Connolly, a historian at Purdue University Northwest* in Indiana who has made an extensive study of the two siblings.

In Ohio, they started the settlement house called Santa Maria and helped Italian immigrants pass their citizenship tests. They also established churches, a day care center and a credit union, among other accomplishments. By that time, in the wake of a World War I campaign to Americanize immigrants, Italian Catholics were well integrated into the population.

Mary Beth Fraser Connolly, a historian at Purdue University Northwest* in Indiana (Courtesy of Mary Beth Fraser Connolly)

"To become good Catholics was to become Good Americans," Connolly described it. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Catholics were also fighting to keep their immigrant populations in the fold.

"Blandina and Justina believed all good Italians were Catholic. They wanted to evangelize and took every opportunity they could, particularly if they came across a mixed marriage," she noted.

While hostility towards Catholics and the nuns who represented the faith ebbed, hostility towards immigrants persisted.

The Immigration Act of 1924, which set strict quotas on the number of immigrants allowed to enter America, may have had the consequence of limiting the number of sisters entering the country but did not target them, said Rzeznik.

Ironically, taking immigration off the table as a potential anti-Catholic tool may have allowed for fuller acceptance and integration of Catholics, including those who arrived in waves from Eastern Europe and Italy during the 1880s and '90s.

Arriving in New York City in 1889, Mother Cabrini, who had founded the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Italy in 1880, opened schools and orphanages in the United States for Italian immigrants. This is thought to be the last photo of her. (Courtesy of the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus)

The national immigration restrictions of the 1920s allowed immigrant groups already here to assimilate, suggested Rzeznik. "That's very much part of the story of Catholics in the United States when immigration restrictions cut off new waves of immigrants. The process of Americanization becomes more pronounced, and that's happening within the religious communities as well."

Overall, he said, the type of anti-Catholicism (and thus bias against nuns) seen in the 19th and early 20th century is largely a thing of the past.

While isolated incidences of bias may persist (Readers can still purchase Monk's Awful Disclosures online), sisters now work closely with ecumenical and interfaith organizations. Widely accepted, many battle against bigotry once directed against them.

One sign of how well accepted and even revered sisters had become was an editorial in the 1936 Salt Lake Tribune provided by Holy Cross sister and archivist Sr. Catherine Osimo. It mourns the death of Holy Cross Sr. M. Beniti O'Connor. An Irish immigrant herself, O'Connor spent more than 30 years working at the sister-founded Holy Cross Hospital in Salt Lake City, one third of that span as mother superior, according to the newspaper. She had also helped build medical facilities in Utah, Indiana and New Mexico.

The editorial writer eulogized O'Connor as: "one of those, self sacrificing women who renounce worldly pleasures, aspirations and allurements to devote their lives and talents, their entire time and every thought to the service of the Savior, the advancement of their church, the betterment of humanity and the alleviation of suffering."

In language that might have been stridently offensive to anti-immigrant activists of the 1830s, the author went on:

Admired for her native intelligence and acquired wisdom, revered for her piety and devotion to duty, beloved by members of the medical and nursing professions, she was recognized wherever known as one of those ministering angels who are now and then permitted to visit the earth. It is not necessary to accept the faith, to join in the devotions, to attend the religious services of such a woman to acknowledge her worth or render the homage due exalted souls consecrated to the cause of mercy, of compassion, of kindness whose energies are exercised for the physical, mental and spiritual amelioration of mankind.

Once despised, even feared, orders founded by immigrants had won the hearts of a wary America by doing the work that needed to be done. They had arrived.

*An earlier version of this story gave the incorrect university branch.

Coming Thursday in Part 2: Sisters nowadays directly assist or advocate for migrants and refugees knocking on America's door who face the same prejudice immigrant Catholic nuns once did.