Moved by the way Catholic sisters at her high school loved and cared for all the students, Tariro Chimanyiwa decided to join the convent.

“When my elder sister, who was responsible for my school fees married, her husband said she could not continue paying for my education,” Sr. Tariro Chimanyiwa recalled. “I told Sr. Hildegard Zahnbrecher, a Dominican sister who was the school head at the time, and she said the mission would pay for me.

“That gesture touched me so much. I couldn’t believe that people who were not related to me would do something so selfless. I knew then that I would also want a life of service to others.”

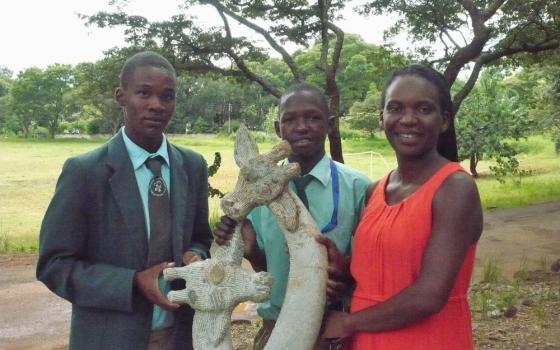

More than four decades, later, Chimanyiwa, a Domincan sister, is still serving children at Emerald Hill School and Home for the Deaf on the outskirts of Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare. Sr. Tariro, as she is affectionately called by the children, is a warm, soft-spoken woman who started out as a teacher 34 years ago and now heads the school.

Emerald Hill is a sanctuary for both deaf and hearing children, bringing together orphans and children from various parts of the community. Situated on a hill populated with indigenous trees, the school is imposing with red brick and tile. Dominican sisters maintain and run the school but receive government support for finding teachers and paying their salaries.

Traditionally, deaf children have not had it easy in this country. Some parents focus more on their hearing children because they are ill-equipped to care for ones with special needs.

Emerald Hill gives deaf children the opportunity to sharpen both their signing and vocal communication skills. Chimanyiwa and the teachers at the school help the deaf children see beyond their hearing impediment. They are encouraged to believe in themselves and explore their academic and technical skills.

The school’s educational program runs from nursery school through primary school and through Ordinary Level, the fourth year of a six-year secondary school curriculum, and vocational training.

“Our children leave school with an O-Level certificate and a National Foundation Certificate, which enable them either to go into business for themselves or be employed,” Chimanyiwa explained.

“We try to impart as many survival skills and as much knowledge as possible. One of our current students is a member of the junior parliament, and six former students have trained as teachers and want to come back to teach here.”

But like so many orphanages and schools in Zimbabwe, Emerald Hill faces many challenges. Some of the children come from low-income families who are not always able to pay the U.S. $480 tuition and boarding fees, per term. The money also covers food and any special equipment the children need.

“The challenge in running the school has always been: ‘How do I get through the month with the money that I have?’” Chimanyiwa said. “I also say, ‘On this mountain, the Lord provides.’ There are times when you say, ‘Where am I going to get the wages?’ but from somewhere the Lord says: ‘Don’t worry. I will look after my own.’ And it works out in the end.”

Chimanyiwa now does less teaching and focuses on administrative work.

“There is that worry of not having savings. We always have very little money but we have never gone hungry,” she explained. “We may go without certain things but we always have the basic necessities.”

The school relies on donors, though there are not many now because of Zimbabwe’s economic slump. Over the past few years many companies closed for reasons that included lack of capital, obsolete machinery and also because of unclear ownership policies. (Any company with a turnover of more than $500,000 must be 51 percent owned by local, black Zimbabweans).

Chimanyiwa pointed out that, although grateful for help from donors, she hoped that one day Emerald Hill would be self-sufficient. The school has a poultry project, a cornfield and a vegetable garden that supplies the school. Excess produce is sold to the local community.

The children are encouraged to participate in sporting activities, musicals and church programs run by other parishes. Some also participate in children’s rights activities run by the non-governmental organisation, Justice for Children.

Her day starts at the break of dawn with prayers and ends well after the children have settled down for the night.

“Knowing that we have equipped them well for the outside world makes it worthwhile,” Chimanyiwa concluded. “We want our children to become responsible citizens who can care for themselves and others. When I see that I’m happy.”

[Grace Mutandwa, a Zimbabwe-based international journalist, columnist, editor and mentor who was recently recognized by the U.S. Embassy in Harare and the Humanitarian Information Centre for exemplary conduct and dedication in promoting gender equality in the media.]

Related - Q & A with Sr. Tariro Chimanyiwa