Hilda Ramirez heard the immigration official pounding on the door and calling her name.

She whispered to her roommate. “Tell him that I’m in the bathroom.” But the officer came back twice as Ramirez cowered with her 9-year-old son at an immigration detention facility in Karnes City, Texas.

“I’ll be there right there,” she called when he knocked a third time. Ramirez knew that when officials called your name, it either meant a scolding or deportation. So the young Guatemalan mother, who had been in detention with her son, Ivan, for 11 months, ran to call her lawyer.

The attorney, she said, laughed. “’You’re getting out. I’m coming to get you this afternoon.’”

But freedom came with a price, she soon found out. After signing papers and listening to instructions, an immigration official presented Ramirez, whom ICE considers a flight risk, one more item.

“Un grillete,” she said. An ankle monitor.

“I felt a little strange,” Ramirez said. “I felt like you only put those on criminals to keep them under control. I wasn’t in agreement, but at least I was getting out.”

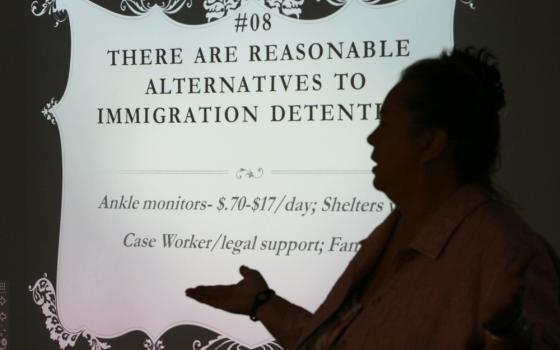

Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers are increasingly using practices described as alternatives to detention, or ATD, to keep tabs on immigrants released from their detention facilities. The most common alternative methods used by ICE are electronic monitoring by ankle bracelet and telephone check-ins.

Immigrant advocates often describe the ICE approach as an alternative form of detention, not an alternative to detention. Instead, they promote reasonable bail, access to lawyers and community-based efforts.

Over the years, non-profit and faith-based organizations have cobbled together unique programs for asylum-seekers that vary from city to city and from one organization to another. While ankle monitors are inhumane and stigmatize the user, advocates say, community-based alternative programs are better than incarceration, lead to high rates of appearances at court hearings and are much cheaper to run.

Ramirez and her son, who had no family or friends to lean on, found a place in a program called Casa Marianella. Tucked behind tall cacti at the end of a tree-lined street in Austin, Texas, the green wooden structure and its companion home across the street has space for 38 but now houses 46 people, some who sleep on the floors.

While Casa serves single men and women, it offers a second program, Posada Esperanza, for women and children. And that’s where Ramirez eventually ended up, on a cul-de-sac, sharing space with residents from all over the world.

Like other community-based programs, residents are free to come and go whenever they want.

“We are not a detention [facility],” said Jennifer Long, Casa Marianella executive director. “We’re a hospitality house that provides services to enable people to move on to the next step and begin to resettle here and prepare their cases.”

In addition to housing, Casa provides legal services, access to low-cost or free health care, psychological help, English classes, help with court appearances (generally called case management services) and acupuncture and herbal medicine.

“A lot of people are victims of torture and political violence so we try to get people hooked up with the right community resources and maybe seek out some psychological resources,” said Rebecca Daily, a Jesuit volunteer from Fordham University who is in a year of post-graduate service at Casa.

“What we have at Casa, we have many things,” said Mohammed Omar, a Somali immigrant who fled his country after masked gunmen killed his father as the two sat outside at sunset. “We have support; we have freedom. They show me that they love me, and they show me a humanity.”

Electronic monitoring more common

In recent weeks federal officials announced plans to end the long-term detention of most migrant families, as political and media scrutiny over the Obama administration’s family detention practices spiked. Court action is expected any day that could lead to the release of most or all mothers and children in ICE’s three family detention centers.

Advocates say they’ve already seen a marked increase in the numbers of women and children released from two detention centers outside of San Antonio. At the Greyhound bus station last Tuesday night, 20 families lined up for bus tickets. Several women scrambled about trying to find outlets to charge their ankle monitors.

Ankle monitors are a key tool ICE uses to keep tract of other immigrants released from detention across the country. While more than 31,000 detainees are held nationwide, more than 24,000 women and men are in some kind of alternative detention, according to ICE statistics.

In addition to electronic monitoring, ATD programs at 75 locations nationwide use a combination of home and office visits and court monitoring with contractor support, ICE said.

The main contractor is BI Incorporated, a subsidiary of GEO Group that runs some of ICE’s detention centers, including the one in Karnes City. “The leader in offender monitoring,” says a slogan on its website.

“Those who are not subject to mandatory detention and do not pose a threat to the community may be placed on some form of supervision as part of ICE’s Alternatives to Detention [ATD] program,” ICE spokesperson Jennifer Elzea said in a statement. “The utilization of ATD enhances appearance rates in immigration court proceedings, increases compliance rates with final orders and reduces absconder rates.”

The use of ATD programs may increase after a federal lawsuit challenging the detention of families is resolved. Talks between opposing attorneys broke down Friday, so the next action will come from the judge. If she sticks to her tentative ruling that family detention violates a previous court order, many women and children could be released and placed in these programs.

Building networks

Housing is a key piece of the puzzle for advocates running community-based programs for immigrants. Molly Corbett, who runs Asylee Women Enterprise, a non-profit program in Baltimore that serves women asylum-seekers, found hers in an unexpected place.

The program for 14 women, which includes a few released from detention, began four years ago when Corbett needed a place for a pregnant Afghani woman. She found it in a Benedictine convent. Now she matches asylum seekers with congregations of women religious.

“The role of the sisters is really crucial,” said Corbett, because “sisters know how to live in community.” In turn, having women and children fill some of the convents’ empty rooms brought in a special synergy. “It brings so much life to the convent or monastery. It’s a win-win.”

Sr. Katherine Corr, a Notre Dame de Namur sister agreed. “We all receive from these young people, from their courage and perseverance.”

The sisters were also willing to commit their space for long periods of time. When the pregnant Afghani woman needed a place, Corbett asked the Benedictine sisters to take her for a couple of days. “That turned into two-and-a-half years.”

Because it takes several years for immigration cases to be resolved and for women to get settled, residents can stay in their living quarters for two years after asylum is granted, longer than most programs in the country. Asylee Women Enterprise has a long waiting list.

“We provide a long enough time period that someone can have savings, can build a network in the community, can get a job that pays,” Corbett said.

“We consider what we do really like a ministry of presence, as opposed to sort of a case management model,” Corbett said. But, she added, the program’s focus on helping immigrants find living-wage jobs has kept 80 percent of participants from needing any sort of government assistance after they leave.

Although some community and faith-based ATD programs operate separately from ICE, others recently partnered with the agency through pilot programs coordinated by the United States Conference on Catholic Bishops and the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service.

The bishops’ one-year pilot tested a community-based program for 50 people. “We proposed that we would serve the most vulnerable individuals and try to provide alternatives for the folks that do really poorly in detention,” said Hilary Chester, associate director of the USCCB’s Migration and Refugee Services.

Among those targeted were victims of human trafficking and torture, asylum seekers, the elderly, individuals with medical and mental health concerns, unaccompanied minors and LGBT individuals who are often “victimized and stigmatized by other detainees and the staff,” Chester said.

The program ran in two cities – Baton Rouge and Boston – and was self-funded with money from an anonymous Catholic donor and internal funds, not federal dollars, according to Chester. Modeled after the bishops’ Refugee and Resettlement Program, immigrants often roomed with refugees and shared other services, such as legal assistance.

“I think it was successful in that the people that we had released and that we assisted are certainly better off out of detention than in detention,” Chester said.

The Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service program began in May 2013, served 46 people and took a different approach. “In each of the communities, we work with partners who have absolutely different models,” said Liz Sweet, director for Access to Justice at LIRS.

Among their partners were Casa Marianella, American Gateways, RAICES and the Interfaith Committee for Detained Immigrants, organizations that Sweet said provide shelter-type environments, housing through host families, or case management services.

The Lutheran project does not accept ICE funding either, though it recently bid on a contract that the agency opened up to non-profits and others. That program will provide funding for “family case management services” in five cities: Baltimore, Chicago, Miami, New York and Los Angeles. The programs will serve a minimum of 40 heads of household but no more than 300, according to the bid document for Miami.

The Interfaith Committee’s project in Chicago houses a total of 35 men, women and children at a convent and in a student residence. It also offers case management services that help immigrants living outside their shelters stay in compliance with ICE’s check-in requirements.

Edith Osorto, a Honduran mother who was detained with her son in the same Karnes City facility as Hilda Ramirez, found out how crucial those services could be. She moved twice, and although she said she sent a change of address form to ICE, her check-in notice arrived eight days late. Osorto cried.

An Interfaith Committee volunteer helped Osorto fill out new change of address forms, write a letter explaining what happened and make copies, and promised to send the documents and assist in finding a lawyer.

“I could not have done this without her help,” said Osorto who feared being sent back to her home country. “It’s not that I don’t want to go back to Honduras. I can’t go back to Honduras.”

What happened to Osorto is typical, said Linda Brandmiller, Ramirez’s attorney and founder of the Asociación de Servicios para el Inmigrante. “If they don’t go, it’s generally because they didn’t get the notice,” she said. “If they miss, they are afraid to show up.”

Navigating the process

Critics opposed to the release of immigrants from detention have long expressed fears that they are going to abscond.

But case management services offered by community-based programs, like the one in Chicago, have shown high rates of compliance among former detainees. Several directors reported compliance rates of 100 percent while others were in the high 90s.

“We asked ICE one day at a meeting what our responsibility was; what if somebody just disappears? And they said, ‘You don’t have responsibility except to let us know that they’re no longer in your program,’ said Sr. JoAnn Persch, a Sister of Mercy and executive director for the Chicago organization. “But we’ve never had to do that.”

Most community-based programs offer services to help residents comply with ICE check-ins or court appearances. At Casa Marianella, volunteers shuttle different residents to San Antonio for check-ins about two to three times a month, said Daily, the Jesuit volunteer. The 165-mile round trip usually takes about four hours, factoring in wait times. But the actual appointments – a face-to-face visit and signature on a page – only take minutes. Residents go about every six months

Similar numbers have been reported in ICE’s ATD program called the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program that relies heavily on electronic monitoring. “Per ICE records through June 2014, 99.5 percent of individuals enrolled in the Alternatives to Detention program showed up for the scheduled immigration court appearance,” Elzea said in a statement. “The appearance rate, especially for final hearings during that same time period, was 94.7 percent.”

The average costs for running ICE monitoring services of all types is about $5.34 per person per day, Elzea said, compared to the cost of detention which averages to about $129.54 per day in 2015. Since most non-profits use private funds, there is no cost to tax payers.

But advocates also say a simpler option can work, too.

“Many, many people don’t need a program of any kind,” said Mary Small, policy director for Detention Watch Network. “An affordable bond can be just as effective as some community support programs.”

Small acknowledged that a bond doesn’t provide additional support like having an attorney and good information.

“An attorney is really there to help them navigate the process and make them feel a sense of comfort,” said Michelle Mendez, Training and Legal support staff attorney for the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Inc. “When you have that feeling as an asylum seeker who has experienced violence and trauma, that can make a huge difference.”

A TRAC Immigration Project report released in February found that immigrant women and children who did not have a lawyer only won 1.5 percent of their cases compared to those with representation, who had a 26.3 percent win rate.

“There are regular Americans who don’t know how to navigate the court process here,” Mendez said, “so bring in somebody from another country who’s never been here, who doesn’t speak the language, and you can imagine how much harder it is for that person to navigate the process on their own.”

Two hours, twice a day

The harshest criticism from advocates, though, is reserved for ankle monitors, which they say humiliate immigrants by making them look like criminals.

“They’re bulky and discriminatory,” Brandmiller said. But, “if the only choice that the government gives is detention or an ankle bracelet, an ankle bracelet is still better than being in prison.”

Brandmiller recently asked Ramirez to join her and speak about detention at a meeting. As Brandmiller talked, Ramirez sat at a nearby table with her ankle monitor plugged into the wall, charging. She must do that twice a day, each time for two hours.

Privately she said, it hurts her foot, but that doesn’t seem so bad compared to her friend who feels electrical impulses through her legs. When she goes out, she said she feels embarrassed by the device. “The people look at me and ask, ‘What is that?’”

When she spoke, Ramirez described her first moments of freedom with her son. Brandmiller took them to Dairy Queen and Walmart and gave Ivan a stuffed bear.

Later, as they ate grilled chicken at JJ’s Café in Seguin, Texas, a waitress named Andrea Contreras handed Ramirez her tips, about $65, and apologized that it wasn’t more. Brandmiller said she and the accompanying social workers burst into tears as they explained the gesture to Ramirez.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Ramirez said. “I cried with joy and I couldn’t believe that someone would do something so nice for us. It was beautiful. Unforgettable!”

Then Ivan told them he had decided on a name for his bear. “Andrea.”

[Nuri Vallbona is a freelance documentary photojournalist. She worked for the Miami Herald from 1993 to 2008 and has been a lecturer at the University of Texas and Texas Tech University.]