On a recent Tuesday morning, Sr. Magdalena Pascual stood in front of an open black metal door and looked toward the woman inside. The woman wore red platform shoes, black leather hot pants, a red T-shirt and black vest. She was 30 years old but had the weary look of someone much older.

A bed behind her with one white sheet caught the pale glow of a bare lightbulb that hung from the warped ceiling. Cracks in the walls rivered toward a mirror hanging beside a calendar. A broom and a bucket stood in one corner.

"How are you?" Pascual asked the woman. "I haven't seen you for a while. I hope you're OK."

"I'm working another place one block down," the woman said and pointed. "I'm making my best effort to get by."

Pascual, a diminutive woman in sandals with long, dark hair, squinted above her glasses and handed the woman a slip of paper that said, "Make your best effort and be brave."

"The saying for the day," Pascual said.

The woman read it.

"Yes," she said after a moment. "I try to be brave."

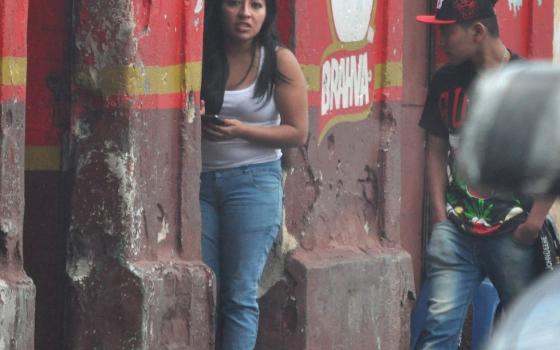

Pascual, 33, is one of six Oblate Sisters of the Most Holy Redeemer who does outreach work on La Línea, "The Line," Guatemala City's well-known, notorious red-light district. Seven days a week, nearly 24 hours a day, as many as 250 women or more ranging in age from their early 20s to mid-60s work as prostitutes on a barren, two-block stretch of grim row houses where a weed-covered train track divides the bleak street in half. The women solicit business standing before darkened, windowless rooms that resemble storage containers and that reek of sweat and garbage and mildew. They work alone without pimps, but they must pay powerful local gangs a protection fee every few days if they want to stay in business and not suffer consequences that can range from beatings to death.

Police can be seen passing through La Línea, but for the most part, the city has turned its back on this place and on the women who work there, leaving it to property owners who charge the women by the day for the use of each row house and to the criminal gangs demanding protection fees. The women live on the periphery of the capital, ignored, disdained and vulnerable, part of an illicit world from which they struggle to survive earning about $4 to $6 for every 15 to 20 minutes they spend with a john. Older women earn just $2 per "ride."

"The women going into prostitution do it as a last resort, a last option in their lives," said Sr. Rosa Maria Suarez, director of the Guatemala City office of Oblate Sisters of the Most Holy Redeemer, which opened in 2010 to work with the capital's prostitutes. The order's mission is to work with women involved in the sex industry.

"They do this work for economic survival," Suarez, 46, said. "Behind each of these prostitutes is a complex, sad and profound story we don't know about unless we meet these women and talk to them. We must take our shoes off and put on theirs and see into their lives."

Unlike other organizations that work with prostitutes, the order does not harangue the prostitutes about leaving the street. Pascual said the order has no agenda other than working with the prostitutes to make their lives as safe as possible. Should those efforts lead the women to seek help, the order will work with them to achieve whatever goals they set for themselves.

"We are not harassing them," Pascual said. "We are not telling them what to do. Other programs say, 'Fill out these forms and do this.' The women get bored and resentful with these conversion efforts. We know when to talk to them and walk away. Our message is, 'We care for you as you are.'"

Her colleague, Sr. Maria Enriqueta, worked with prostitutes in Mexico and Colombia for 29 years before the order transferred her to Guatemala City in 2012.

"For me and the other nuns, La Línea is a sacred place because it is where we do our mission work," Enriqueta, 54, said. "No one else sees it that way. No one sees the women, period. Even the church. Our Lady of the Rosary is nearby, a major tourist attraction, but no one cares about these women. No one looks in this direction. Even the priests choose not to see them."

The sisters invite the prostitutes to Our Lady of the Rosary to celebrate Mother's Day and other holidays. On those occasions, the priests provide them an area separate from other parishioners.

"But at least they let them in the church," Enriqueta said.

Although the sisters consider La Línea a sacred place, they remain very aware of its dangers. Women have been found murdered there. In one instance, on a television news broadcast, the sisters saw a blood-spattered room on La Línea with one of the inspirational cards in it. The woman had been stabbed and strangled and found three days later stuffed beneath her bed. Why she was killed is unknown.

She was a single mother in her 20s, Enriqueta said, and had worked as a prostitute because she had been unable to find other work. A witness to her death was found dead three days later.

"La Línea is a tough place," Enriqueta said. "The whole environment is heavy. When a girl dies, all the women are sad. They ask, 'When is it going to be my turn to die?' "

Cognizant of the risks, Pascual prays to God and to her deceased mother for guidance when she sets out to meet with the prostitutes every Tuesday and Thursday. She has done outreach on La Línea since 2014, and still the odors of the street and its filth make an impression: the sharp stink of bleach the prostitutes use to clean their rooms; the funk of their cheap perfume; the gasoline fumes of men on motorcycles racing in circles through the street, sometimes on the sidewalks, to see which women are available or if a woman they consider their own has found other customers. The mix of roaming johns and the stomach-turning smells, Pascual said, can make her dizzy.

Pascual remembers the first prostitute she met on La Línea. The woman worked from a room in the middle of the row houses. She had her guard up as Pascual approached her. Pascual asked her if she had children. The woman said she had two boys. They discussed how the boys were doing in school. Talking about the prostitute's children provided a safe middle ground for Pascual and the woman to feel one another out and gain one another's trust. Pascual has followed that approach ever since.

"I have done this for a year and a half," one woman told Pascual on a Tuesday morning as Pascual stood outside her row house on La Línea, the black metal door open to the street. Inside the dank 9-by-12-foot room, a faded, curling poster promoting the use of condoms caught a sliver of dim light below a small, wooden crucifix.

"I take care of two daughters," the prostitute said. "Before, I only did this on special occasions. But now I have no other work, and I do this Monday through Saturday. My mother watches the children."

"Take care and be careful," Pascual said.

Outside, beside Pascual, a man sat on a cinder block with a closed shoe-shine box and looked at the ground, chin in his hands, his thoughts lost in his blank, hopeless stare. The woman said he is a regular on the street who takes advantage of the foot traffic to earn money polishing shoes.

In the past year, more and more indigenous women have been working on La Línea, Pascual said. She herself is an indigenous woman from Santa Cruz Chinautla, a mountainous region in northern Guatemala. The indigenous women tell her they left their homes looking for work or fleeing domestic violence, including rape and incest.

"I feel a great sadness," Pascual said. "What comes to my mind are the huge traumas in these communities that force women to leave. They let go of their roots to make a little money here."

Besides outreach, the Oblate Sisters of the Most Holy Redeemer run a center for prostitutes open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Friday. There, the women can relax and do nothing if they choose, or they can see a counselor and make greeting cards to sell as an alternative to working the streets.

"I am planning to leave this life in October," Sandra, 25, a prostitute, said at the center. She is the mother of three children, ages 9, 4 and 3. "I can't leave now. In my case, I have a $140 debt to pay for a bed I bought for my children."

After she pays her debt, Sandra said she hopes to get a well-paying job, perhaps as a waitress or a cook. She grew up in Nicaragua and moved to Guatemala for work in a maquiladora (sweat shop) in 2006. She met a man, the father of her three children, who abandoned her when she became pregnant with their youngest child, she said. She took a month off from work after she gave birth to their third child and lost her job. Unable to find work, Sandra said she turned to prostitution.

"When your children are hungry, they can't wait for you to get a decent job," she said.

Angelica, a 45-year-old prostitute, said she was a housewife for more than 30 years when her drug-addicted daughter abandoned her three young children. Angelica took them in. With an alcoholic, unemployed husband, she resorted to prostitution to support her grandchildren.

"At my age, I can't get other work," she said. "Today, I went to see about a job as a cook in a restaurant. They asked for letters of recommendation, a list of where else I had worked, what my education was. I wasn't accepted."

Sandra and Angelica said their families do not know they work as prostitutes.

"At the end of my day, I see my kids and hold them," Sandra said. A friend watches them during the day. "They see me and come out to me. 'You're here, Momma.' I hug them. I am tired. The entire day I've been stressed, but I still have my kids."

Angelica's grandchildren run to her, too.

"'You're finally home,'" she said they tell her. "I want to sleep, but they won't let me. Sometimes they have not eaten. I tell my husband, 'How did you let them go through the day without even a piece of bread, a tortilla or an egg?' I feel tired, and if the day was slow, I am sometimes angry because I have not earned enough for the children."

Still, she knows in the morning, she will go out once more to La Línea.

"This work is the worst thing there is," Angelica said. "Most of the time, you get men who smell and ask you to do nasty things. Old, young, addicts and drunks. You need to fake pleasure and do what they want. Maybe I can take the children and leave the country for the United States. Anything but this. I can't stand this."

Pascual and the five other sisters at Oblate Sisters of the Most Holy Redeemer hear these stories and cries of desperation almost daily. They listen. They don't preach or pass judgment. And if the prostitutes ask for help, they do for them what they can.

"I admire them," Pascual said of the prostitutes, "their inner strength to move forward in life and their struggle to beat anything, even death. Our goal is not to get them off the street. We look at them as people, not a soul going to heaven, not a soul needing to be saved. We care about them, just them as they are, and their well-being. Our preaching comes from doing the small things."

[J. Malcolm Garcia is a freelance writer and author of The Khaarijee: A Chronicle of Friendship and War in Kabul and What Wars Leave Behind: The Faceless and the Forgotten. He is a recipient of the Studs Terkel Prize for writing about the working classes and the Sigma Delta Chi Award for excellence in journalism.]