The olive trees on the Mount of Olives next to Jerusalem's Garden of Gethsemane stand gnarled and silent, their knobby trunks reaching out of the rocky hills, a testament to thousands of years of careful cultivation in one of the holiest spots on Earth.

This four-acre olive grove belonging to Benedictine sisters looks out on the golden rotunda of the Dome of the Rock, glinting in the sunlight, and the walls of ancient Jerusalem following the contours of the hills and wadis. From the grove, their trees stand witness to the path Jesus took to the Garden of Gethsemane on the night of his betrayal.

But the Benedictine Sisters of Our Lady of Calvary, who have inhabited this old stone convent for the last 120 years, also see another side of the historic olive grove: the Jerusalem municipality water bill.

A few hundred meters away, on the other side of the hill from the Benedictines' monastery, Jerusalem descends sharply into the desert, sparse vegetation giving way to barren rocks until you reach the Dead Sea, Earth's lowest spot on land. This proximity to the desert also means that the olive trees need buckets and buckets of water — about $2,500 of water per month and sometimes even more in the brutal summer heat.

Cisterns are an ancient method of collecting rainwater in underground stone caverns for household use and irrigation. The Benedictine compound has more than 20 cisterns, though they had fallen into disuse and no longer functioned. By renovating them and reverting to the traditional method of capturing rainwater, the sisters will cut down dramatically on their use of municipal water.

"We knew we had cisterns here, so the sisters tried to repair them but it didn't work," said Sr. Gabriele Penka, 38, who is originally from Germany but has been in the Jerusalem convent for the last 10 years. "We thought it would be hard to find someone to rehabilitate them."

A cistern renovation requires a unique blend of technical, historical and archaeological knowledge, not to mention that a full-time "cistern restorer" might have difficulty getting enough work, even in a place like Jerusalem.

But the pontifical mission the Catholic Near East Welfare Association had contacts with appropriate engineers in Bethlehem. Along with funding from the French group Knights of the Holy Sepulcher, the sisters undertook a $56,000 renovation of five of their cisterns last winter.

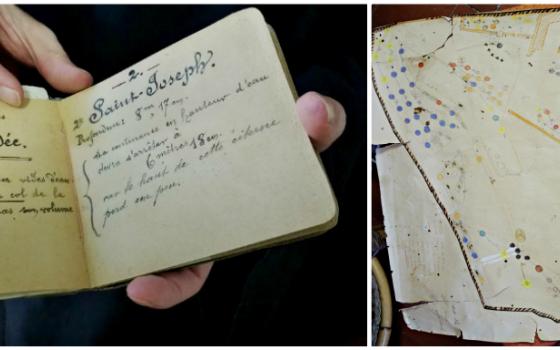

"In our early documents, they mention that the cisterns are a big wealth for the house and the congregation," said Penka, who oversaw the renovation. That leadership position also turned her into a de facto congregational historian as she pored over hand-drawn plans from the early 19th century to assist the engineers. "Now we're connected to the municipality water, but before that there was no water, and there are no springs in this area, so [having cisterns] was really necessary."

The convent is in the Ras Al Amud neighborhood of East Jerusalem, which has changed hands half a dozen times in the last 100 years. When the Benedictine Sisters first arrived in the 1890s, it was under Ottoman control. From the end of World War II to 1948, the area was under the British Mandate, then under Jordan from 1948 to 1967, and under Israeli control after 1967. Palestinians hope it will be part of the capital of a future Palestinian state, though Israeli authorities are unlikely to relinquish this or any part of Jerusalem in a two-state agreement. The convent was hooked up to Jerusalem municipal water after 1967.

Centuries-old history on the Mount of Olives

"We believe the cisterns are from the sixth century, and that maybe there was a Byzantine monastery here," said Penka. "One of our cisterns is more rectangular. Usually cisterns are like a round bottle. This one and another one are rectangular. We think maybe it was a burial place."

Religious life on the Mount of Olives started as early as the fourth century. St. Melania the Elder (325-410) fled her wealthy Roman family to become a religious ascetic and built two monasteries on the Mount of Olives, one for women and one for men. The exact locations of these two original monasteries are unknown, said Joseph Patrich, an archaeology professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem who has studied the area. St. Melania the Younger (383-439) followed in her grandmother's footsteps and built additional monasteries on the Mount of Olives in the fifth century, where she lived until her death.

In 640, after the Muslims led by Omar the Kaliph conquered the area, most Christians left the Mount of Olives. Christians returned during the Crusader period from 1099 to around 1200. After Saladin conquered the area in 1187, Christians also began to flee the area and did not return for centuries while it was under Muslim control.

In the 19th century, many Christian and Catholic congregations began to return, including the Benedictine Sisters. There were more than 100 monasteries and convents in this neighborhood in the early 20th century, and many still remain, though with smaller populations.

"Without archaeological excavations, it's hard to know exactly what was in this spot," Patrich said of the Benedictine convent. "The cisterns could be from the Byzantine period, from as early as the fourth century."

Patrich said it is likely that the Benedictine convent was built on top of previous religious buildings. "There were a lot of important convents and monasteries in this area," he said.

Semicloistered amid the crowds

The Benedictine convent is also unique because it is a semicloistered convent in the midst of one of the most impoverished and crowded East Jerusalem neighborhoods. Next door to the convent is a contentious Jewish settlement called Beit Hoshen, run by the group the City of David Foundation, whose ideological agenda is to purchase land in Arab neighborhoods and build heavily fortified Jewish residences, in an attempt to "Judaize" the area. Ateret Cohanim is a fringe group in Israel and its practices are condemned by mainstream Israelis, though embraced by the extreme right. Beit Hoshen is a single building with about 30 people.

"One year before I arrived, the [Beit Hoshen] building was sold," said Penka. "The [Palestinian] farmer owner lost his life. People don't like when you sell to Jews" in this neighborhood, she explained.

The location of the Jewish building means the road is now a flash point for riots whenever the political situation becomes shaky. Additionally, the sisters are located on the road toward the Mount of Olives, the holiest place for Jews to be buried, because it is believed that the arrival of the Messiah will come from the Mount of Olives and those buried there will be the first dead to be resurrected. But many Arab residents resent the endless traffic jams from funerals. Angry children and teenagers protesting the Israeli occupation sometimes throw stones at the Jewish people's cars exiting the cemetery. In the very middle of all this tension are a high stone wall and a small blue steel gate, with the words "Benedictines" carved into the tan pockmarked Jerusalem stone.

"There are lots of incidents on the Mount of Olives, the clashes have become more visible, more violent," said Penka.

"You can hear the clashes. During the last war with Gaza [in 2014, which also led to unrest in East Jerusalem], we could hear the clashes, and you could smell the tear gas. It's a little strange; on the one hand, we know what is happening and yet we are not really connected," she said.

"Monastic life — it is not just the wall in itself, which is to mark a certain separation," said Penka. "It should also be a kind of inner attitude. It doesn't mean that you're not interested in what is going on, but that you try to keep a certain distance and try not to be overwhelmed by what is going on outside."

"Sometimes I wish for more quiet," Penka added. "We are more or less in the middle of a city, and so there's the usual noise of cities. I visit monasteries in France; you can go out for a walk and see green. Here you're immediately in a group of pilgrims or people walking."

Penka said the urban cloister is also challenging in the spiritual dimension. "You need more conviction," she said.

Unlike other monasteries, where the calmness or beauty of a rural setting helps sisters find quiet and balance, the Jerusalem convent does not have that luxury. "The exterior doesn't help, so you need a stronger interior," said Penka. Sisters in the convent must draw deeper into their own reserves to achieve quiet and serenity amid the urban din, as well as amid the occasional tear gas and rock-throwing.

Carefully structured days

The Benedictine convent is "semicloistered," which means sisters can leave for specific tasks, such as buying supplies, administrative duties or flying home for occasional visits. They do not leave the convent grounds casually, instead receiving a "benediction" to leave for a certain reason each time.

The day at the convent is carefully structured, punctuated by three main prayer sessions, which add up to more than five hours of contemplative or community prayer each day.

"The most important thing is to search for God, these things are trying to help us, it's the main theme of our lives," said Penka. "We don't go out there so there are no distractions."

Previously, the sisters ran an orphanage for Greek Catholic girls on the grounds until the 1970s. When the Benedictines came in 1896, there were already a number of French contemplative orders or sisters in Jerusalem, so the church representatives asked the Benedictines to start the orphanage in order to serve the community as well as make a gesture of solidarity from the Latin Catholics to the Greek Catholics.

However, as the need for orphanages diminished, the sisters reverted to the traditional Benedictine convent, which generally does not provide social services such as schools or clinics, Penka said.

Today, one sister is a talented icon painter and leads workshops on her art, which bring in some income. The convent also sells icons and a variety of religious artifacts made on site, as well as products from their garden, including olive oil, lemon jam and lavender potpourri. They give tours to visiting groups of French pilgrims or host young volunteers in their Spartan basement quarters.

"We have employees for gardening and cleaning, which is also a way to have more relations with the people here," said Penka. "Even if we don't go out, we still get all the news."

The first test for the cisterns

This winter's rainy season will be the first test for the cisterns, as they were completed toward the end of last winter after the heaviest rains. The rainy season in Israel is from December or January to April. One thing that Penka discovered in her research is that the sisters named each cistern — one is called the Child Jesus, another is called the Virgin Mary, others are named after various saints. It's a sign of the sisters' appreciation for the life-giving importance of water.

After the cisterns are up and running, Penka is looking forward to being able to walk in the garden without cringing because someone accidentally left a hose running. "They said it will be drinking-water quality, but most of the sisters here are worried about that, so we'll still use municipality water for drinking and cooking," she said.

Even if the winter is dry and the cisterns fail to fill, the olive trees won't be in danger. "We don't have a problem that maybe there won't be water, because we'll stay connected to the municipal water supply," she said. Still, the cisterns could pose significant savings in the coming years.

At 4:30 p.m. exactly, Penka returns to the chapel, a cavernous stone hall filled with stained glass and brightly painted icons. She rings a bell that echoes through the convent, and the other six sisters file into the chapel for afternoon prayers. As their voices soar, filling the hall with phrases of French and Latin, outside the convent walls, the Muslim call to prayer starts. Recordings announce the beginning of afternoon prayers from speakers atop minarets sprinkled throughout the neighborhood, each scratchy recording a half-second behind its neighboring mosque. At the Jewish cemetery, a group chants the mourning prayer to mark the anniversary of the death of a beloved rabbi.

The musical supplications of the three religions rise and fall, weaving a tapestry of sound that echoes down the rocky hillside. The prayers, carried on the wind, rustle the leaves of the olive trees, as they have for centuries.

[Melanie Lidman is Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report based in Israel.]