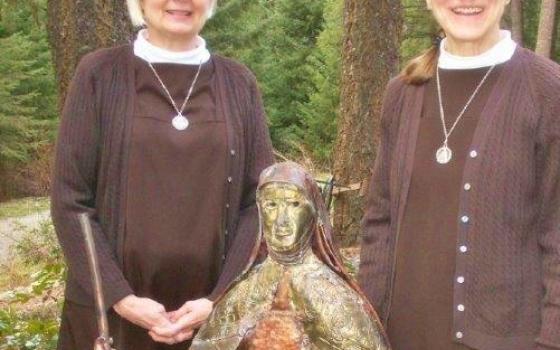

To understand what brought. Carmelite Sisters of Mary Leslie Lund and Nancy Casale to seek holiness and solitude as hermits in the northwestern wilderness of Washington a quarter-century ago, it’s helpful to take the long view — 800 years of long view.

Though both spent many years of devotion residing in communal monasteries with other Carmelite nuns, it was their desire to live more fully the spirituality of the monks of Mount Carmel that led the two of them, literally, into the wilderness, to seek “the original charism,” that of the first Carmelite hermits.

In the early 13th-century, a group of men sought guidance from Albert, then Patriarch of Jerusalem, to dedicate themselves to solitary penance and prayer on Mount Carmel (part of a mountain range in Northern Israel). Within decades, however, these hermits were spurred by the changing politics of the medieval Middle East to move to Europe, becoming mendicant friars and often practicing a less stringent way of life.

(During the medieval and Renaissance periods, female members of the order always resided behind monastery walls, Lund said.)

The reforms of Teresa of Avila, intended to restore some of the rigor of the original eremites, eventually set the stage for a separate order known as the Discalced Carmelites. It’s not at all clear, suggests Lund, that Teresa (named a doctor of the church along with her compatriot John of the Cross) wanted to start a separate order.

“We were formed in the monastery, but we wanted to lead a less institutional and complicated life, to go back to the original expression St. Teresa had in mind, of nuns that were also hermits,” Lund said.

While some might argue that a life of prayer is insufficient to cope with the reality of the world’s brokenness, Lund suggests that prayer itself is healing. “The Teresian charism is really that Christ is the center of our lives, our prayer is friendship with God.” In praying for the world’s transformation, she said, “We have a great concern for the need and suffering in the world. It’s not a flight from it. We think we are at the heart and root of the world . . . not through one specific ministry, but through our prayers.”

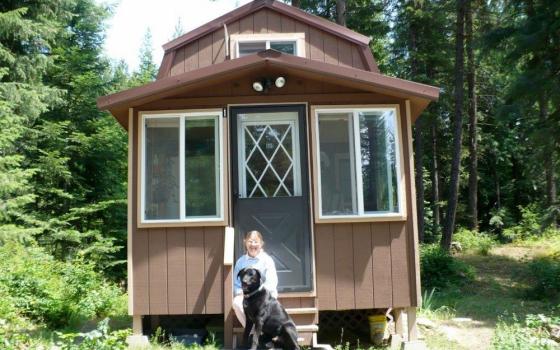

Set in the mountains in an area dubbed the “Appalachia of the West,” according to the community’s website, the 80-acre tract includes a central building with guestrooms, surrounded by five hermitages, where Lund and Casale welcome other nuns, secular Carmelites, diocesan clergy and apostolic sisters for private retreats and spiritual direction.

As custodians of many acres of woodland, Lund and Casale have become well known locally for their devotion to environmental stewardship, which they see as part of a wider mission to a needy planet.

“Teresa wanted to live a simple and poor life of detachment, humility and love,” Lund said. Balancing a call to solitude and community, she and Casale meet four days a week for prayer and Communion and attend Mass on Sunday in a parish church. (There is only one priest for five county parishes in this region.) The other three days are spent in solitary reflection. Each day includes, in harmony with the Carmelite rule, two hours of contemplative prayer and an hour of spiritual reading.

The two nuns also find time to meet with their guests, some of whom seek spiritual direction and some simply utter solitude.

“It just depends,” Lund said. “It seems like we’ve helped a lot of people in transition from one monastery to another, or from a monastery to hermit life, whatever is needed.” Some visitors come for a week — one stayed two years. Whether traditional, progressive, or somewhere in between, “We try to welcome all of them and provide what they need.”

In the years that preceded her move to Washington State in Discalced Carmelites monasteries, Lund said, “I was blessed to live among open-minded, deep-spirited and holy women.”

While there might have been tension between those of the older Carmelite branch, known as the Order of Ancient Observance, and the Discalced, those have dissipated with time, she said. “They are meeting these days and growing in unity, learning that unity is not always the same as uniformity. We are all one in the eyes of God.”

Carmelite monasteries are autonomous, she added. Without a mother general or a superior, “The character and personality of the monastery is dependent on the people who are there.”

While Carmelites have a range of lifestyles and practices that run the gamut from a strictly enclosed life to one that allows for external retreats and family visits, women from different monastic foundations have reached across lines and become friends, she said.

For hermits, Lund said, they are very busy, “but we’ve asked Teresa to help us.” That’s particularly appropriate this year, the 500th anniversary of her birth on Oct. 3, when Casale and Lund traveled through the diocese talking about (and in Lund’s case, using acting to make her point) their famous foundress. “We hope to be manifesting our charism this way.”

Though some nun friends have been working on finding a place for them in one of the Carmelite associations, Lund said that they don’t feel a pressing need. (They are currently under the jurisdiction of the bishop of the Spokane diocese.)

While they aren’t actively seeking other hermits to join them, they remain open to God’s call, if it’s the right fit.

“Our real desire is, in deepest payer, that all may be one,” she concluded. “Our world is so divided.”

[Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans is a religion columnist for Lancaster Newspapers, Inc., as well as a freelance writer.]

This is the fifth profile of a six-part series called Contemplative Communities.

Click here to see the introductory article, the other four commuity profiles, and two related columns.