Canossian Sr. Melissa Dwyer chats with one of her high school students at Bakhita School in Balaka, Malawi, in 2009 (Photo courtesy of Melissa Dwyer)

Sr. Melissa Dwyer, congregational leader of the Australian province of the Canossian Daughters of Charity, received an honorary doctorate from Australian Catholic University on April 5 in recognition of her work as an educator and a promoter of educational opportunities, particularly in Malawi, where for seven years she led 600 girls at Bakhita Secondary School in Balaka Township.

The Canossian Daughters of Charity were founded in Italy in 1808 and now minister in 35 countries. There are some 2,300 sisters worldwide, but only 32 in Australia. The congregation's ministries are centered around serving people in poverty and making Jesus known and loved.

Dwyer was appointed leader of the Australian sisters in May 2019 at the age of 38, and her leadership term was renewed in February 2021.

In a past life, Dwyer dreamed of a different kind of honor: an Olympic gold medal for athletics. Javelin was her strong suit. But, as she says, "God has ways."

GSR: What role did sport play in your early life in Brisbane?

Dwyer: Involvement in sport was a very big part of my childhood. I was only 5 when I first went to Little Athletics. I was very dedicated and spent a lot of time training. Dad was my coach until I reached senior high school, when he felt he couldn't offer me any more, so I began with a new coach.

Canossian Sr. Melissa Dwyer poses in 2009 with students at Bakhita Secondary School in Balaka, Malawi, where Dwyer served as principal for seven years. (Photo: courtesy of Melissa Dwyer)

I did well academically but I didn't spend a lot of time studying. Athletics, netball, cricket, hockey, tennis — all these were very time-consuming.

I always wanted to be a physical education teacher; that was the dream. I certainly had no intention of becoming a nun!

Was the church an important part of family life?

To be honest, growing up, I used to run away from church. I would come up with every excuse to avoid going. Mum would take us to Mass on Sunday, but we weren't a family that prayed together — we didn't pray the rosary, for example — and Dad wasn't a churchgoer.

It was only when I finished school that I reached a point where my faith became my own. I was 16 when I completed Year 12. I moved from the safety and security of school into university to study to be a physical education teacher. I soon realized that no one cared whether you were there or not at university and I became lost in that.

I reached a point where I didn't like myself. I had very low self-esteem, although I had plenty of friends, I'd done well at school, I was in the degree I wanted to pursue, I was really good at sport. However, inside, I felt empty, and it was only then that I came to a personal relationship with Jesus.

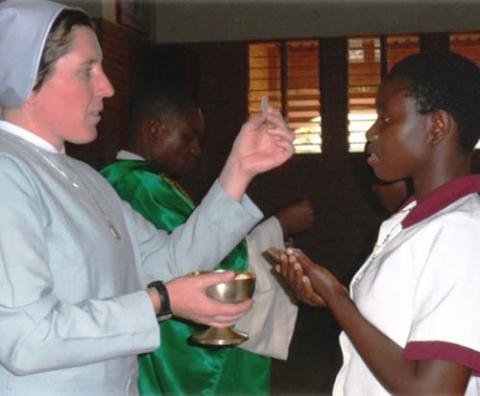

Canossian Sr. Melissa Dwyer administers the Eucharist at a Mass at Bakhita Secondary School in Balaka, Malawi, in 2011. (Photo courtesy of Melissa Dwyer)

I became involved in the local church, and three years later, I was discerning a call to enter religious life. It was all a bit of a whirlwind.

How did the Canossian sisters enter your picture?

I was happily in a relationship and training seriously for my sporting career. I went to a Sunday evening Mass because I was competing during the day. At the back of the church, there was a brochure about retreats for young adults led by the Canossian sisters, although that meant little to me at the time.

I participated in a couple of retreats — ironically, retreats I now help to facilitate — and through them I came to know the sisters and they came to know me. This led to their asking if I would be interested in a volunteer experience, accompanying a group of young people traveling to Rome for World Youth Day 2000. I asked if there would be an opportunity to volunteer in one of the missions in the developing world, so Tanzania was tacked on to my World Youth Day experience.

You were on target to be selected for the Sydney Olympics — a home crowd! — but you went instead to Rome and Tanzania. What was the impact of visiting Tanzania?

Tanzania turned my world completely upside-down. I went to Africa out of curiosity, to see if the media image of Africa was real. I shared life in a community with homeless young people, and while it was enriching, it led to a great sense of frustration with God because I felt there was nothing I could do to help them.

'I didn't look. I entered. I had no idea what community life might look like, but I was just radically committed to giving my life completely in serving God and serving those in need.'

The night before I was due to come home, I felt really annoyed with God. A little girl had begged to come with me to be my servant, to carry my bag and tie my shoes, and there was nothing I could do for her. I said to God, "Why am I so useless?" I don't like to be unable to fix things.

It became apparent to me through prayer that there was something I could do: I could give my life completely to God and completely to the poor by becoming a Canossian Daughter of Charity, a servant of the poor. So I did. It was a real Paul-falling-off-the-horse moment.

How did the people in your life react to this momentous decision?

I told my parents, and they took a long time to accept it.

I told my coach, who never spoke to me again.

I didn't know the first thing about religious life, and I said to a priest, "Maybe I should look at other congregations?"

He said something very profound: "Mel, no matter how far you look, where you first find peace is what you'll ultimately come back to."

I didn't look. I entered. I had no idea what community life might look like, but I was just radically committed to giving my life completely in serving God and serving those in need. I still am.

Canossian Sr. Melissa Dwyer with villagers in Balaka, Malawi, in 2009 (Photo courtesy of Melissa Dwyer)

What did you learn about the sisters as you began to live their life?

In Australia, poverty takes many forms, not only material poverty, so in our discernment of a ministry, we ask: How are we making Jesus known and loved, and how are we serving people in need? We have sisters working with refugees, with different ethnic communities, sisters who are counselors, social workers, nurses, psychologists, ministering in parishes and to Italian communities who appreciate their familiarity.

Since entering in 2005, it hasn't always been easy; there have been lots of challenges, plenty of ups and downs, but every day, there's a growing awareness of the gift of the charism that's been entrusted to me.

How were you asked to use your particular gifts in service of the charism?

My postulancy and novitiate were both in Brisbane. I completed my degree in physical education, and after four years of initial formation, I made my first profession of vows. I then taught for three years at St. James College Spring Hill here in Brisbane.

Then I was asked to go to Malawi in East Africa as a junior sister. I had to get the atlas out to see where on earth I was being sent!

Canossian Sr. Melissa Dwyer with children in a village in Balaka, Malawi, in 2009 (Photo courtesy of Melissa Dwyer).

I didn't choose Malawi. We can say we prefer to stay in our country of origin or we can be ad gentes, available to the people. I declared myself ad gentes. I spent three months in a very remote village community learning the language, then another three months in the school before I was appointed principal.

It was hard.

Malawi is considered one of the poorest countries in the world, and for young girls, education is not accessible. Very often, the girls at our school would not just be the only one in their family with a chance at secondary school education, but perhaps the only one in their entire village. They are in the classroom before 5 a.m. and they leave the classroom at 9 p.m., six days a week.

There was great joy for me in the African experience, and I'm not joking when I say I'd go back tomorrow. And yet, there was culture shock; I was young, I was alone, I didn't meet another Australian for eight years. You are living with other sisters but you always stand out because you're white. Having to earn the trust of the staff, families, students probably took about three years. It was important they not see me as a colonizer.

Canossian Sr. Melissa Dwyer's senior English class at Bakhita Secondary School in Balaka, Malawi, in 2015. (Photo courtesy of Melissa Dwyer)

Bible knowledge was taught, and I introduced values education to try to give the girls a more holistic experience. The education system is very much about rote learning, all geared to preparing for three weeks of exams at the end of schooling.

In your address following the conferral of the doctorate, you shared the story of Christina, who had an enormous impact on you.

Christina came to our school at the beginning of Grade 7. Shortly after, her mother and father both died of AIDS. Within months, Christina came to know that she herself was HIV-positive, having contracted the disease before she was born from her mother.

Christina became very angry, blaming her late mother for what she called her death sentence. Then Christina herself became very sick, spending weeks in the hospital with pneumonia and tuberculosis. It was a hospital with 50 people crammed in one room, only eight beds, no fans or air conditioning.

Every evening, I would go to the hospital and sit on the floor with Christina, feeding her boiled potatoes, which is all she would swallow. As I sat on the floor with this 12-year-old girl, I had no words to console her. I simply listened and tried to help Christina find peace in her heart.

Advertisement

After four weeks, Christina was able to realize that her mother didn't mean to make her sick. Literally the day after she was able to forgive her mother, Christina began to put on weight. Despite still being very unwell, she was able to come back to school.

For the next four years, I did all I could to encourage Christina to pursue her dream of studying law. In a country where so few females ever have the chance to go to university, I didn't believe it would be possible. Yet, like any good teacher, I encouraged her. I saw Christina graduate from Year 12 in 2016 before I returned to Australia.

In 2019, Christina sent me a list of names of students who had qualified to study law at the University of Malawi. Christina's name was there. She has completed her initial studies in law and is working in a legal firm in Malawi.

What brought you back to Brisbane?

Again, my life changed very quickly. After nearly eight years, I had a missed call from Italy. Mother-General was asking me to come back to Australia to be part of the leadership team. I asked for some time to pray, and she said she would call back at 9 a.m. the next morning.

'It was incredibly hard to come back. I didn't know you could have reverse culture shock.'

I couldn't tell anyone, and after a sleepless night and lots of prayer, I asked her, "Do you honestly believe this is what God wants?"

She said, "I don't claim to know fully the will of the Lord, but as far as I can know, I believe this is what God wants." I said I would come back to Australia.

Was it a wrench to leave Africa despite the challenges there?

It was incredibly hard to come back. I didn't know you could have reverse culture shock.

After two months, I was given the opportunity to go back and finish teaching my Year 12 class — that was a gift. I'd been leading a school, and things had been tracking really well in Malawi, and the ministry here — sitting in an office and checking minutes of meetings — was less satisfying. I think I fell into a period of depression.

Eventually, I took on some external ministries with the St. Vincent de Paul Society and vocations promotion in the archdiocese, and that helped enormously, but I gave the majority of my time to serving the province as an assistant.

In 2019, I was appointed leader of our Australian province.

Canossian Sr. Melissa Dwyer with a class at Bakhita Secondary School in Balaka, Malawi, in 2015. (Photo courtesy of Melissa Dwyer)

How did you respond to this appointment?

I'm certainly grateful for the trust that's been placed in me by my sisters and by the General Council in Rome.

I went to Africa at 27, a young white woman in a patriarchal country, to lead a school. That was a challenge, and it broke a stereotype. I'm one who likes to break stereotypes, so I'm blessed to have the opportunity to step into that space again.

Now, as a leader of women, I'm calling on the same discipline, the same commitment, the same passion and desire to do my very best that I had as a young athlete and when I entered religious life.

How would you describe your style of leadership?

It's about not asking anyone to do anything I wouldn't be prepared to do myself. It's servant leadership, and I hope my sisters would say the same if you asked them.

When I was principal in Malawi, I was teaching 30-plus lessons a week because my title was head teacher. I believe very much in setting a good example, walking the talk.

Authenticity is very important to me. If, for example, I'm encouraging my sisters to live a life of prayer, and I'm not living a life of prayer, there's something incongruent in that.

Martin Daubney, chancellor of Australian Catholic University, with Canossian Sr. Melissa Dwyer after being conferred her honorary doctorate degree in April 2022. (Photo courtesy of the Australian Catholic University)

Education has been a key thread throughout your life, and now you've been given a university's highest honor.

I remain very humbled by the honorary doctorate, and I dedicated it to the people of Malawi, the people at the grassroots who gave me the opportunity to walk with them. It gives me an opportunity to highlight the need for quality education in so many parts of our world.

I'm also committed to religious life. I believe passionately in our charism, and I'm convinced that religious life is a valid choice for women today.

Formation is an important part of my leadership role. I believe God's asking me to teach in a different context. I'm responsible for the sisters' ongoing formation.

We have 11 sisters under the age of 60, so we do have life. I have received two young women into the congregation.

Even though it's challenging and it was really hard to come back from Malawi, I believe I'm doing what God's asking.

Finally, do you ever think about throwing a javelin again?

It's certainly part of who I am. It's part of my narrative. It's not something I hook on to in any way, but the values I hold now were born and took shape on the sporting field, so I'm grateful for that season of my life.

If it's a connection point for young people to be able to say, "Hey, it doesn't matter what you do, God can call you to religious life," then that's a bonus. I would want it to be a positive lens that opens the minds and hearts of young people to say, "If she can do it, then so can I."