Cars in Coyote Canyon, New Mexico, on the Navajo reservation, line up to receive food at a food distribution point before the start of a weekend-long curfew May 15 during the coronavirus pandemic. (CNS/USA Today Network via Reuters/The Republic/David Wallace)

I remember this story so well. I was a young teacher in Derry, Northern Ireland, and was always on the lookout for global stories to help our war-torn youth to look out and beyond the pain of the "Troubles" to find signs of a more compassionate common humanity.

I invited my brother, Don, to speak to our students at Thornhill College in Derry. He was the director of a Dublin-based human rights organization addressing the historical neglect of Ireland's Great Famine, when over 1 million souls were consigned to unmarked mass graves.

It was during this talk that he told the students about how the Choctaw tribe in the U.S. had helped the poor Irish, and he encouraged the students to "look out" beyond our geographical world and the commonality of the human experience in oppression.

The Choctaw story aroused a great deal of interest among the students and, as a result, three busloads of students and staff (120 in total) traveled 160 miles to Doolough, Co. Mayo, in the western part of Ireland in May 1990, to take part in a famine commemoration walk.

Advertisement

Tribal leaders from the Choctaw community led the group to remember a tragic walk undertaken by hundreds of destitute souls during Ireland's Great Famine. At the beginning of the walk, the students, my mother and family watched as my brother was given a headdress of feathers and was named an honorary chief of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma in recognition of his contribution highlighting this remarkable story.

The 1990 Irish Walk adopted the name "The Trail of Tears," which told the story of the 500-mile death march from Choctaw ancestral lands in Mississippi to Oklahoma. The Choctaw were forced to make that journey in 1831 as a result of the U.S. government policy of Indian removal during the presidency of Andrew Jackson (himself a son of Scots-Irish immigrants).

The "Five Civilized Tribes" inhabiting the Southeastern U.S. (Choctaw, Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek and Seminole) were forced to move to the Oklahoma Territory under pressure from white settlers who had encroached their lands in violation of existing treaties. The Choctaw were the first to depart. Unprepared for the hardships of the journey, begun in December 1831 (one of the worst winters the South had seen), more than a quarter of the Choctaw population died of starvation, exposure and disease.

In 1847, only 16 years after the beginning of Choctaw removal in 1831, the Choctaw learned of the plight of the Irish people 4,000 miles away. The Arkansas Intelligencer and Niles Weekly Register recorded a meeting in Skullyville (in the Oklahoma Territory), where a collection was taken to assist the famine victims in Ireland. Some reports say $170 was raised from meagre resources by the Choctaw for Irish famine relief. The 1990 walk, with the opportunity to listen to Choctaw representatives tell their story, was a teachable moment for the students. The young people were also exposed for the first time to the inherent decency of a Native American tribe instead of the "savages" so often documented in cowboy and Indian movies.

The year before the walk, Don had traveled to Ada, Oklahoma, to thank the Choctaw and to invite the leadership to lead the Famine Walk the following year. They said it was the first time that anyone, since 1847, had connected with the Choctaw people to thank them.

Since then, the modern links between the Choctaw and the Irish have continued to grow. Former Irish President Mary Robinson — who would later become UN High Commissioner for Human Rights — traveled to Oklahoma in 1995 to thank the Choctaw people. She too was named an honorary chief of the Choctaw Nation.

I recall Robinson saying that the Irish would always remember with gratitude the compassion and concern displayed by the Choctaw Nation who, from their distant lands, sent assistance to the Irish people in our time of need.

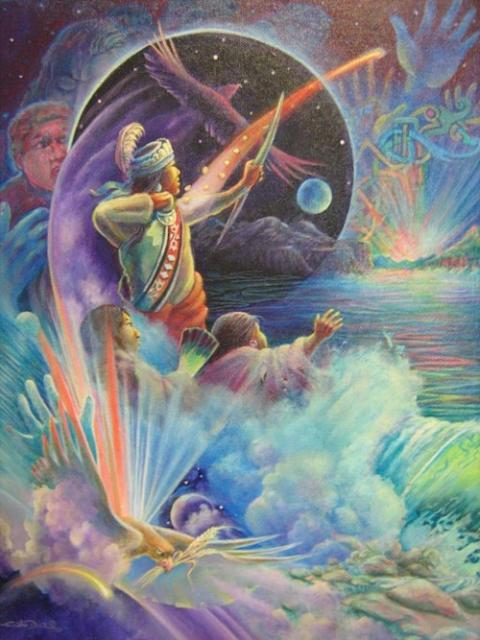

"An Arrow Through Time," painting by Choctaw artist and author Waylon Gary White Deer (Courtesy of Waylon Gary White Deer)

Choctaw artist Gary White Deer was a frequent visitor to our home in Derry since he loved our mother's cooking. Gary often remarked that when we reach out to each other we feed our own spirits as well.

The destiny of our two peoples had become intertwined and continues to do good today. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, ravishing our broken world, this story has again surfaced into Irish consciousness. Little did we realize what the Choctaw story told when they led the Famine Walk in 1990 would awaken in the Irish worldwide.

On May 4, in response to the Navajo/Hopi COVID-19 appeal, many of the donors recalling Choctaw generosity during the Great Famine reached out with reciprocal solidarity.

Initially, the GoFundMe appeal sought to raise $1.5 million for vital equipment. At the time of writing, that has been exceeded, with almost $4.1 million raised, the majority from the Irish donors.

The Navajo/Hopi leadership were deeply surprised by the generosity of the Irish people, as they were unaware of the Choctaw-Ireland connection until the donations began to flood in. I heard Cassandra Begay, a member of the Navajo Nation who helped to organize the fund raising speak on RTE 1 (Irish National Radio) and she remarked that the many donations coming from Ireland caused her to ask why.

Then she learned about the Choctaw story recounted above.

It is often said of the Irish that we never forget. The list of donors to a GoFundMe page is testimony that Ireland remembers. The Choctaw people reached out over 173 years ago when Ireland was in deep crisis and now many Irish people are responding in kind.

The pandemic is a timely reminder of the importance, and inherent power, in saying "thank you."

But we have more work to do!

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit the Native American community hard, and the Navajo Nation has now surpassed New York and New Jersey for the highest per-capita coronavirus infection rate in the U.S. — another sign that the pandemic is having a disproportionate impact on minority communities.

How might we as a human community respond?

[Mercy Sr. Deirdre Mullan of Ireland served as the executive director of Mercy Global Concern at the United Nations for more than 10 years. In 2011, she became the director of The Partnership for Global Justice, a network of over 125 small congregations at the U.N. Her present ministry is working with UNICEF to look at ways in which they can partner with religious communities.]