Benedictine Sisters pray Vespers together at St. Scholastica Monastery in Chicago, Illinois, on New Year's Eve, 2020. (Belinda Monahan)

"That's so nice of you!" I stood at the other end of the phone dumbfounded as the nurse said these words to me. I had called the clinic asking for a copy of my positive COVID-19 test results because I wanted to see if I could give convalescent plasma. To hear a nurse at a clinic, which was providing tests and healthcare to dozens of congregate living communities along with low-income individuals, tell me how nice I was being seemed strange and out of place. Much of my experience of COVID-19 in the monastery was like this: Things that had been familiar felt suddenly off-kilter. The weeks in which the residents of the monastery were ill were difficult but also filled with a strange grace as I experienced the support of an extended community.

It started Easter Sunday morning. My community had celebrated a quieter than usual, socially distanced Triduum, only to be wakened near dawn by notes being slipped under our doors that someone had been taken to the hospital the night before and tested positive for COVID-19. We were to remain in our rooms, our meals would be brought to our doors, and even more shockingly, in a monastery, all liturgies would be suspended.

Advertisement

The next week or so is a blur. Our kitchen and nursing staff continued to come in and take care of us, preparing meals for us to take back to our rooms and tending to the needs of our sisters in the infirmary wing. We worked out schedules for picking up our own meals, carefully masked, and for disinfecting our shared bathrooms. By Friday, one additional sister had gone to the hospital, we had our first round of tests back (nearly two-thirds positive), and the clinic I had just spoken to was coming to test the rest of us.

As I sat in the chair that we had set up in the hallway, it was a comfort to hear the team who went from room to room on all four floors to administer the tests, laughing and observing that they'd never otherwise get the chance to see inside a monastery. While the experience seemed utterly surreal to me, the kindness and generosity of the doctors and nurses made it easier and far less scary. That weekend did not feel like the Second Sunday of Easter. We watched helplessly as ambulances took two more sisters to the ER, waited for our test results and tried to work out a more detailed plan for isolating the sisters who were sick and for quarantining the healthy ones.

By the time I received my positive diagnosis, it seemed like an anticlimax. Again, what stands out most was the gentleness of the prioress as she told me and the kindness and generosity of the doctor who called to officially notify me. I remained largely asymptomatic, continued much of my work remotely, and was able to leave self-isolation two weeks after my diagnosis. I received care packages of cookies and books and things to keep me busy. Far harder than my own illness was watching other community members become ill and worrying about those sisters who were high risk (which was nearly everyone except me). In all, 20 of the 28 of us residing at the monastery eventually tested positive; eight spent some time in the hospital and two died from the disease.

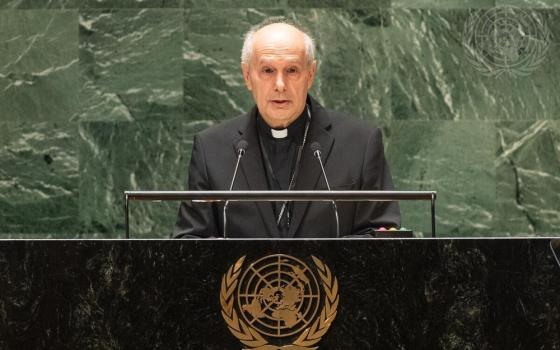

The Benedictine Sisters of St. Scholastica Monastery in Chicago, Illinois, began community meetings with a memorial service in summer 2020 during the pandemic. (Belinda Monahan)

More than eight months have passed since our first community member tested positive. We are returning to "normal," but it is a new normal. Almost as soon as our two-week quarantine was over, a small group of sisters rearranged the chapel and began attending liturgy regularly. Slowly, much of the rest of the community also returned to liturgy, distanced even farther apart and masked. We were able to celebrate Christmas liturgies together — quieter than usual, with no guests. Several sisters have returned to limited work schedules outside of the monastery. Much of the community eats lunch and dinner together in the dining room.

Yet all of us are also changed by our experience. I have grown in appreciation of my dependence on God and in gratitude for the people who support me in my daily life: family and friends who called daily or sent packages; community members and our staff who continued to work to keep us fed and clean. I miss being able to gather for a casual conversation or a quick cup of coffee, but I am also more aware of the deep connections that tie the community together, even in the absence of these social encounters.

I also still stop what I'm doing when an ambulance goes by, to make sure it's not stopping here to take someone else to the hospital, and to say a prayer for whoever is riding in it. A few of us trade tips on the best place to give plasma: where and how to set up appointments, who's fun to chat with, which places feel safest. I do not want to downplay the difficulty of the experience or the grief that we are all experiencing for the community members — along with the hundreds of thousands of others we have lost, among whom are our own family members and friends. But even in these struggles — perhaps because of these struggles — the grace of community has abounded for me.

The Benedictine Sisters of St. Scholastica Monastery in Chicago, Illinois, attend a virtual concert in the chapel in the infirmary wing. One of the community's oblates played piano and sang for the sisters. (Belinda Monahan)