Whenever I visit a monastery, I come away impressed by the prayerful atmosphere and peaceful setting. I notice the colorful arrangement of the gardens and the attention given to the smallest details, like place settings on dinner tables or flowers on the altar.

Often there is beautiful art created by community members. As a Benedictine lay associate, or oblate, I especially enjoy participating in the liturgy of the hours — the prayer life of the community — in which the voices of individual members swell into a single, harmonious, other-worldly sound.

Cultivating beauty is as much a part of the Benedictine monastic tradition as praying the Psalms and seeking God through community. Monks of the Middle Ages famously copied the Bible, using elaborate calligraphy and glowing illuminations. St. Benedict devotes an entire chapter in his Rule to "Artisans of the Monastery." The saint believed that when the hands are occupied, the mind turns to God through the act of creating.

Today, that artistic tradition continues. Sisters and monks have expanded their ancient calling to include woodworking, glass-making, embroidery, pottery, banner-making, photography, felting, knitting, poetry writing and liturgical music composition.

For four years, I've been a part of the American Benedictine Academy, which works to pass on Benedictine values. Our biennial conference this year celebrated modern "artisans of the monastery." It brought together more than 100 artists, writers, musicians, craftspeople and art appreciators at St. Benedict Monastery in Minnesota, including a large number of oblates.

In a culture of mass production, monastic artists remind us of the beauty of what is handmade. They celebrate the importance of individual artists' vision. They help us appreciate that the most beautiful creations come not only from the head and the hand, but from the heart and soul.

Many religious orders have a history of supporting the arts. Most orders boast musicians, visual artists and poets among their members. Few have as long or as sweeping an artistic tradition as the Benedictines.

Benedictine Sr. Monika Ellis of St. Placid Priory in Washington specializes in three-dimensional works using felt and wool. Her multi-colored, imaginatively symbolic liturgical banners on display at the conference immediately captured my attention. I pictured them hanging in my living room at home, which I think of as a "sacred space" for our guests.

Sister Monika calls her artistic work "incarnational."

"My spirit is connected to God when I'm creating," she said. "I make things I hope will bring people to a place of wonder."

The decline in number of Benedictine sisters and monks places pressure on those seeking to pursue art alone. Sister Monika, for example, wears multiple hats. In addition to her art, she works as a spiritual director, musician and part-time liturgist and sacristan for her priory.

Benedictine Sr. Dolores Dufner considers herself one of the fortunate. Her community, St. Benedict in St. Joseph, Minnesota, allows her to focus on hymn-writing. She has published more than 200 hymns — many of them staples of liturgical worship at monasteries throughout the world.

Sister Dolores says she began writing out of frustration. She found many traditional hymns too full of "masculine and militaristic" imagery. "As a liturgy planner, I discovered there was often not a hymn for a particular Sunday that I wanted to sing," she recalls.

Being a composer, she says, informs her life as a Benedictine, which emphasizes cultivating personal humility. "Someone once said to me, 'You want the music to be perfect.' I said, 'No. I want it to be beautiful.' If you aim for beauty, even if there are flaws, what you create can still be very enriching and worthwhile," she says.

St. Benedict's Monastery has a long history with the arts. From 1867 to 1968, its sisters created elaborately detailed liturgical vestments and altar cloths known the world over. That style of work faded after Vatican II, as simplified vestments and altar linens became the norm.

But other forms of embroidery and knitting remain important crafts at the monastery. They are a hit with customers hungry for hand-crafted artistry. Benedictine Sr. Moira Wild, who oversees the Haehn Museum at the monastery — a combination exhibit space and gift shop — says the wool shawls the monastery offers "barely get up for display before they're sold."

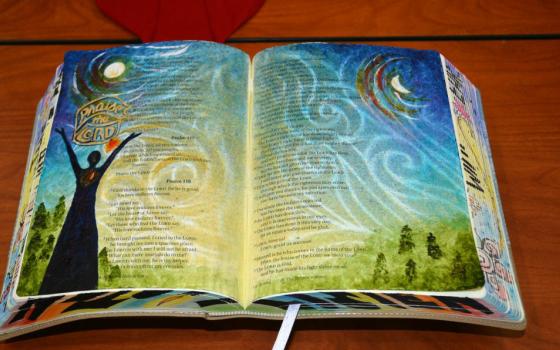

St. Benedict's companion monastery down the road, St. John's Abbey, is another important patron of the arts. St. John's is responsible for one of the most significant public art projects of the late 20th century: the creation of the first hand-lettered, hand-painted Bible in 500 years. This masterwork — a blend of contemporary themes and the ancient practice of illumination — was privately financed and overseen by British master calligrapher Donald Jackson.

While I have seen high-resolution copies of parts of the St. John's Bible, nothing can compare to the vibrancy of the colors and images contained in Jackson's original. Another highlight for me and many other ABA attendees was perusing several books of the original Bible at the St. John's University library.

Increasingly, Benedictine oblates are becoming important bearers of the monastic artistic tradition. Oblates now outnumber professed members of monasteries — 25,000 to 22,000. Kathleen Norris, a poet, and author of the The Cloister Walk and Dakota: A Spiritual Geography is an oblate of Assumption Abbey in North Dakota. Norris says the monastic emphasis on hospitality has made her a better writer.

"Being hospitable to the reader is something the Benedictines have helped me to see as essential to the writing process," she said in her keynote address at the ABA conference. "It helped me get over that teenaged misconception of writing as self-expression. I've learned that the writer is not so much accountable to herself, so much as to the reader."

Maria Ambre, who taught art for 12 years at St. Scholastica Academy in Chicago, says the spirituality of the school's Benedictine sisters influences her work now among public school students.

"I try to help my students understand that the people around them are in their care for that period. That [classroom] space is a community and we care for one another there," Ambre says.

Since their inception, monasteries have had to be self-supporting, and the work of community members remains an important source of income. Sister Monika says her artwork generates $13,000 to $14,000 in annual income for her 15-member St. Placid community — all without any marketing expense.

Still, the pursuit of art for its own intrinsic spiritual value is what most inspires these artists.

Matt Ambre, a visual artist and oblate of St. Scholastica in Chicago, says he keeps above his drawing table a copy of a "Psalm for Work," given to his wife Maria by a Benedictine sister. It says:

May the work that we soon begin be a shimmering mirror of your handiwork in the excellence of its execution, in the joy of doing it for its own sake, in our poverty of ownership over it, in our openness to failure or success, in our invitation to others to share in it.

Words that could well be the motto of all who strive to be both artists and Benedictines.

[Judith Valente is the author of How to Live: What the Rule of St. Benedict Teaches Us About Happiness, Meaning, and Community and the senior correspondent at GLT Radio, an NPR affiliate in Illinois. She is a Benedictine oblate of Mount St. Scholastica Monastery in Atchison, Kansas, and has served on the volunteer board of the American Benedictine Academy since 2014.]