A group of sisters in Nigeria are taking on governors, police chiefs, village chiefs and brothel owners. Under the umbrella organization African Faith & Justice Network Nigeria (AFJN-N), sisters from different congregations and parts of Nigeria made a five-day advocacy trip against violence, particularly the violation of women and children. I was there as coordinator of the main Africa Faith & Justice Network's Women Empowerment Project and as a member of the AFJN-N steering committee.

After hearing reports about the mushrooming numbers of illegal brothels where young and underage girls are trafficked for commercial sex in rural communities in Edo state Nigeria, we were determined to stop these crimes. Having made an advocacy training workshop, we decided to begin a public awareness campaign in two rural communities.

When we arrived at our rallying point, we spent the first three days honing our presentations, mapping out routes, and visiting traditional rulers, the governor, the chief of police and the anti-trafficking unit.

The chief of police welcomed us warmly and confirmed what we had heard about the high incidence of human trafficking and the illegal brothels in the rural areas. He praised us for our boldness and courage in engaging what he regarded as "the big elephant in the room" and pledged his support.

Before going into the villages to meet with the people, we visited the traditional chiefs (the Zaiki), who were delighted to be chosen for the enlightenment program. We also met with key community leaders to learn about their problems and seek their support. We asked the parish priests to encourage their parishioners to attend the gathering. The bishop's vicar welcomed us, loaned us his car for a day, and invited us for dinner one evening.

During a preliminary village visit, we learned about a notorious brothel-keeper whom the villagers were afraid to confront. One of the chiefs said that the brothel encouraged trafficking, sexual exploitation of girls and other social ills. He described his attempts to shut it down and his disappointment when it just relocated to a nearby village. Another chief lamented that every time the owner was arrested, he was released after a few hours.

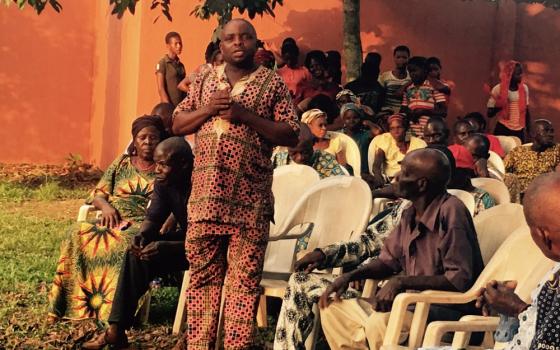

When we arrived in the first village, accompanied by four uniformed police and two anti-trafficking police, the chief summoned the community to his palace. With the parish priest, his catechist, other local sisters working in the area, and over a hundred people in attendance, the chief presented us with kola nuts (a traditional mark of welcome).

The program included a sister social worker, a sister medical doctor, and a sister lawyer. They addressed all forms of violence against persons — particularly against women and children — highlighting the causes, the medical and social consequences, and the legal implications of national and state laws that protect individuals against these crimes.

A female anti-trafficking police officer elaborated on the national definition of violence against the child (including sexual abuse and exploitation, beating, verbal abuse, "bad touching," rape, defilement or sexual abuse of minors, assault of girls, and trafficking). After describing free government legal aid available for victims, she encouraged them to seek redress and taught them how to file child abuse and trafficking cases. Finally, she urged the people to break the habit of protecting the offender, particularly relatives or closer family members.

In an interactive session, the people raised the issue of the illegal brothel. We asked the villagers what they wanted to do about the brothel, but they were silent, and we observed great tension and fear among them. However, the villagers chorused "no" when we asked whether they liked the presence of the brothel in their community.

At the end, an elder thanked us for our concern for their village and their children. The chief thanked us and pledged to work in partnership with us to close the brothel.

Moved by the community's concern, fear, and helplessness, we decided to confront the owner of the brothel before going home. With directions provided by the community, we located it and entered the man's large fenced compound, where we saw him drinking with two friends.

We told him why we had come; he welcomed us and told us that he was a good Christian. He assured us that his place is a registered hotel like any other hotel, and boasted that important men — including top policemen from all parts of Nigeria — come to patronize it. He pointed to a man, identifying him as a police officer who had been staying there for months.

He admitted to having a brothel in the compound, with young female sex workers. We asked if the girls were trafficked, but he became agitated and vehemently refused to answer; rather he insisted that he is bringing development to his community and that he is only providing services for the men who do not have enough access to their wives.

One of the sisters described the moral and legal implications of his activities and demanded that he close the brothel. We asked him to give us a timeline, with plans for closing the brothel and rehabilitating the girls. The owner reluctantly said that he would think about it.

We knew that he was not ready to give up his evil activities, so when we returned to the capital the next day we asked the police to close down the brothel and to rescue and rehabilitate the young women there.

When we arrived at the second village we found the chief and about 300 of his people waiting in his palace. After we repeated the education program, the traditional chief—a lawyer—urged his people not to keep silence: "Silence has stood in the way of fighting a lot of social ills in the community." He warned the community against child neglect and parental permissiveness, and asked his people to stop the practice of child marriage.

The villagers asked about protection for those reporting violence and reporting rape cases without family consent and about how to deal with sexual exploitation by an influential person in the community. We told them when and how information should be shared, and the chief assured them of confidentiality. There was also a discussion on the importance of documentation, and the chief explained how to report sexual abuse, trafficking and violence to state and national agencies.

The community expressed concern over brothels, exploitation, trafficking, rape and armed robbery, and they urged us to extend our work to other communities. The chief thanked us for "remembering" his community, pledged his support, and requested that we continue our work.

As we traveled home, we were excited about taking a public stand against these social evils. We documented our activities, and in subsequent meetings with the governor and police chief we reported our findings, demanding the immediate closing of the brothel, the arrest of the owner, the rescue of the young women, and the rehabilitation of the victims. By the end of this year, we plan to hold other public campaigns, including more outreach programs in the state capital and in rural communities.

The energy and enthusiasm of the sisters, their courage in travelling long distances on unsafe roads, and the support from their major superiors in permitting them to leave their primary ministries to engage in these activities showed me the sisters' vital interest in advocacy ministry.

Lack of funds often stands in the way of advocacy efforts, especially as the impact of advocacy is not immediately felt. AFJN Washington, D.C., and the sisters of AFJN-N are grateful to the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation for providing funds for advocacy training.* The sisters in Nigeria are particularly grateful for this opportunity to actively seek to correct societal wrongs and engage the structures of injustice.

[Eucharia Madueke is a Sister of Notre Dame de Namur in the Nigerian Province with expertise in social analysis, grassroots mobilization and organization. She coordinates the Women Empowerment Project of the African Faith and Justice Network.]

*Editor's note: The Conrad N. Hilton Foundation also funds Global Sisters Report.