Like many others, my oneness with Creation is expressed in sneezing my way into springtime.

I've nestled into an outdoor porch swing, covered with mosquito netting (little critters crawling into my nose are too much oneness!) and have enjoyed predawn concerts of awakening. The stillness is pulsating with expectation and then suddenly, as if on cue, cardinals, mourning doves, nuthatches, black-capped chickadees, red-winged blackbirds and other voices fill the air with song.

My "oneness with Creation" provides a morning liturgy like none other: I can only praise a Cosmic Creator whose evolutionary artistry leaves me speechless.

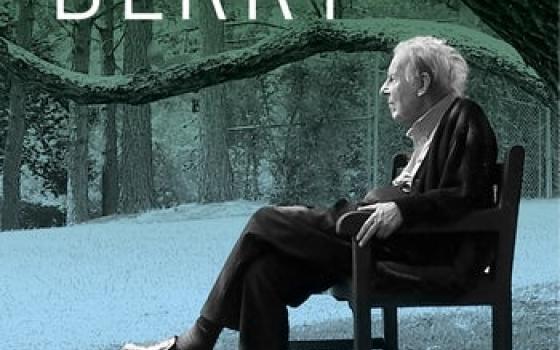

This is the context in which I have read a new biography, Thomas Berry by Mary Evelyn Tucker, John Grim and Andrew Angyal, published on the 10th anniversary of Berry's death on June 1, 2009. This is a book I will return to as my growth in evolutionary consciousness opens me to learn another language, that of the "creation of resilient agricultural systems, bioregions, and ecocities."

It proposes a new story available to all cultures and creeds, translating what we have known into a new language of interiority, diversity and communion, referring to every species having a place in our planetary community. This is called the universe story and includes every species; it welcomes those who have learned the language of spring, outside either cultural or religious creeds.

Building on Berry's love of Creation, contemplation and history, the authors introduce us to a seeker, whose restless heart and profound intellect learned how to rest in the splendid community of Creation. This Passionist priest sought out teachers who would explore with him an array of classic authors — Confucius and indigenous peoples, Dante and Teilhard de Chardin, and many more.

For example, the biographers write, Berry in 1964 "observed that the turbulence of late Medieval Europe evoked creativity from its greatest minds: Dante and others understood that holding the tension of opposing views opened the possibility of more creative resolutions."

"Holding the tension" of opposing views is challenging.

Berry had learned the languages of a new Pentecost many of us prayed for during the Second Vatican Council. As a "geologian," his quest for truth and his desire to educate others were without limit. He studied the geological age of places where he would live and speak, introducing himself out of this bioregional context.

Once he was invited to teach theology to novices and he began with focusing on the importance of place. By holding up a piece of coal, he introduced both himself and millions of years of bioregional history. His recognition of the role of anthracite coal to a bioregion in the Appalachian Mountains gave context to the sisters' education of poor coal miners.

Like his mentor, Teilhard, Berry believed that the cosmic evolution of Creation had to take a central place in the human psyche. Learning to live in harmony with all aspects of our sacred home was his primary concern. He used the term "integral ecology" and Pope Francis heard them as new words in the language of Pentecost hope.

Thomas was also greatly influenced by the wisdom of indigenous peoples. They lived their respect for biodiversity in many ways, by creating liturgies that honored the "tree people," the four-legged ones, the winged people, and our complex and beautiful bioregions. From these sacred traditions, so often misunderstood and destroyed by colonial and ecclesiastical systems, he teaches us the wisdom of native peoples whose vision has never lost the connection between Earth, humans and every aspect of Creation.

Teachers, lawyers, doctors, artists — all of us — are being called to learn this new language of harmony with Earth, recognizing that our extractive, materialistic language of capitalism and consumerism has created a moral crisis that is destroying our precious planet.

The authors Tucker and Grim were students of Berry and have brought his insights to a planetary audience. Their commitment, stamina and fidelity in teaching this new language of the universe story are a gift to all who care about our endangered Mother Earth. Throughout the book, they share their personal love and knowledge of Berry, and also translate his thinking into basic concepts that bring both understanding and commitment to those who hear his message.

"The Great Work," as Thomas called the challenge to live into one's place in a community of Creation, demands new ways of doing things — community-supported agriculture; ecological jurisprudence to protect rivers, mountains and all of nature from an extractive corporate entity; health care and prison reform that recognizes the role of ecological pollution in creating sick and violent communities.

In addition to the biography, Tucker has created a video called "Journey of the Universe," in collaboration with Brian Swimme, another colleague and friend of Berry. Numerous books explore the teachings of Thomas Berry.

How can I/we learn the new Pentecost language of living in communion with all creation? What can we learn from animals or creatures moving toward extinction?

Can we learn their language and respond to the cries of the Earth?

In my reflection on Thomas Berry and my commitment to "care for our common home," I have been challenged by my local Jewish community, the Central Reform Congregation, with whom I often worship.

As I listen to the ways they honor the sacred elements of earth, air, fire and water in services, and see their support of a local food pantry with fresh produce and a community garden, I recognize their understanding of the language of a "new Pentecost" is happening among them.

(Recently I learned that their liturgical practice also includes Pentecost, somewhat different from a Christian understanding.)

We are aware of the Jewish feast of Passover, which celebrates liberation from slavery to freedom, as described in Exodus 12.

However, a lesser-known feast takes place seven weeks after Passover. This is the celebration of Shavuot (Exodus 34:22), also known as Pentecost in Ancient Greek. The Jewish "Pentecost" celebrates the giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai. Through studying and living Torah, they learned the cost of responsibility for their freedom.

So Pentecost for them, Shavuot, recognizes there is no gift of freedom without responsibility. Thus, it marks the event in which the Jews accepted the responsibility to change their lifestyle and become a nation committed to serving God.

Could this be another aspect of the Christian celebration of Pentecost? As we see our neighbors and friends choosing a green lifestyle, perhaps committing to "the Great Work" will lead to a future full of hope (Jeremiah 29:11).

[Judith Best is a School Sister of Notre Dame and coordinator of SturdyRoots.org. She gives presentations on the heritage of the School Sisters of Notre Dame and is also exploring evolution as the bridge between science and religion.]