When I was a small child — or, if I'm honest, even now as an adult — whenever I would find myself in a sticky situation or afraid, I'd return to the first prayers I ever learned, the Our Father and the Hail Mary. The words come naturally and roll effortlessly off the tongue, often at quite a speed. They are comfortable and comforting, and they connect me to something bigger than my worries.

To this day, whenever I wake up from a dark or confusing dream, I find myself instinctively relying on the words of the Hail Mary to return me the present moment. Holy Mary, mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.

These days, during our collective sticky situation of the polarization and fragmentation of our civic society and even our church, I have been drawn to pray the Our Father. The familiar comforting words, however, have started to hold a larger call for me.

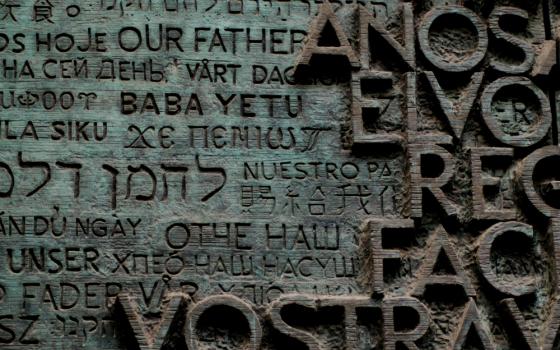

Our Father. Our daily bread. Forgive us as we forgive. Lead us. Deliver us.

This prayer that for decades I have said desperately at my most lonely hours calls us to be community. It is not a prayer to my Father for my daily bread and my forgiveness or deliverance. It is a prayer for the whole. As I have prayed this prayer anew in these days, I haven't been able to get this sense of the collective out of my heart and mind. The hour for "our" is now.

In giving us this prayer, I think Jesus is desperately calling us to remember that we, all of us, even those we most vehemently disagree with, are at our most foundational level beloved children of God. As Sister Sledge sings out loud in the classic dance song, we are family.

Through this simple prayer, Jesus calls us to remember that fact, or re-member — that is, to bring together and reclaim those parts of the whole we'd rather forget or ignore or at least not pay more attention to than is necessary.

Jesus teaches us that when we pray, we are called to pray for the whole and for wholeness, for that which sustains and nourishes community and brings about healing and forgiveness. What better call for our day when there is such polarization, fragmentation and division?

From the very beginning, of course, we've broken apart the whole, even in the early church, where the great debates separated the circumcised from uncircumcised. These divisions take new forms as they persist: rich from poor, blue states from red states, pro-life from social justice, Leadership Conference of Women Religious from Conference of Major Superiors of Women Religious, me from you, us from them.

To be sure, I am not alone in recognizing this urgent call to remember our connectedness. This was essentially the theme of this most recent LCWR assembly, "Being the Presence of Love: The Power of Communion."

"At our core," theologian Heidi Russell told the assembly in her keynote, "we are interconnected to one another and to God, and yet somehow, we find ourselves limited in our relationality, finite in our capacity to connect to one another."

In her book The Source of All Love: Catholicity and the Trinity, Russell further explores this paradox, drawing from the work of physicist David Bohm. Bohm believes that while we experience reality as a whole, we have to break it up into pieces to understand it. This helps us think about things, but it also leads to fragmentation and division when we prioritize "the widespread and pervasive distinctions between people (race, nation, family, profession, etc., etc.) which are now preventing [humankind] from working together for the common good."

Russell notes that what has been a useful thought tool becomes "an obstacle to our understanding the undivided wholeness of our reality."

Even in our most intimate relationships with family, friends and neighbors, she writes, the fragmentation and division of our culture and political scene separates the whole: "We focus on what divides us rather than seeing our neighbor as part of our own wholeness. An electronic age in which people can anonymously write scathing comments, hurling insults at one another from behind the safety of their computer screens, has ripped open the wounds of racism, classism and sexism in our culture."

She concludes it will only be if and when we prioritize "our wholeness in love" that we will move beyond our paralyzing fragmentation.

Love. A nice sentiment, but a hard verb to live.

For the past 600-plus days, I have been trying to love Donald Trump. Each day, as part of my spiritual practice, I pray for him and send him a daily prayer via Twitter. I have no illusions that he reads my daily tweets, but I instinctively knew in the early days of the administration that I needed some nonviolent structure for my own personal reactions to his policies and presidency.

So since January 2017, I have prayed with the news until I could reach a semi-nonviolent, shareable prayer. Tweeting my prayer holds me accountable and I hope adds some positive energy into the world. Don't get me wrong, I am still critical of policies that harm the poor, the environment and our very future. But I also pray for him to experience the love, compassion and mercy of God. I pray he experiences goodness and that this in turn transforms his leadership for the common good.

In the beginning, it was really a matter of "fake it till you make it." But I think this practice is having a transformative impact on me.

We've all been in conversations and circles where legitimate criticism of policy and politics moves into personal attacks, questions of sanity or even humanity, and clever, mean statements about family and anatomy. We may have even contributed to these conversations ourselves out of our frustration, even though they further fragment and polarize the whole.

What's interesting is that increasingly, when I encounter these conversations, I find myself very uncomfortable. Somehow, my prayers that Trump will experience himself as a beloved child of God have helped me to understand and experience him as just that. Instead of disconnection, my practice has led me to a sense of connection, despite the odds.

Surprised as I have been by this transformation on the level of my emotions, it does make sense. Negative energy zaps our energy. Love connects us to the source of all love.

What would happen, I wonder, if instead of spreading negative energy in our conversations that contribute to the toxic levels of our current civic discourse, we practiced loving even those bits of the whole we struggle with? Speaking the truth in love, standing in solidarity in love, acting for justice in love.

Maybe this would lead us to deliverance, provide our nourishment and sustain us, help us to listen deeply for that which binds us together, no matter how small, in the sea of division.

The hour for "our" is now. We just need some daily practice at reprogramming our hearts and minds to experience the whole.

[Susan Rose Francois is a member of the Congregation Leadership Team for the Sisters of St. Joseph of Peace. She was a Bernardin scholar at Catholic Theological Union and has ministered as a justice educator and advocate. Read more of her work on her blog, At the Corner of Susan and St. Joseph.]