An energetic crowd of over 100 people celebrated National Catholic Sisters Week at an intergenerational seminar, "Race and Grace: Let's Talk About It," on March 12 at Mount Augustine in Richfield, Ohio. Some were turned away because of the unexpected number of registrations.

"Many of us in this room today are old enough to remember the civil rights movement of the 1960s," Notre Dame Sr. Carol Dikovitsy said as she welcomed attendees. "But we had no idea of white privilege. . . . It will take more than laws to help us build Martin Luther King's 'Beloved Community' of justice, equal opportunity and love."

Sponsored by a coalition of Catholic groups including, among others, the Sisters of Charity Foundation, the Diocese of Cleveland, the Coalition with Young Adults, the Conference of Religious Leadership and National Catholic Sisters Week, the event drew a rich mixture of neophyte and experienced activists, including women and men; young and old; and black, white and Hispanic attendees.

The event was one of over 150 held nationally March 8-14 to celebrate the contributions of Catholic sisters. The theme of racism grew out of the social justice focus of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, which represents 80 percent of U.S. Catholic sisters.

Co-facilitator Erica Merritt began the discussion by quoting from feminist author bell hooks' influential book Killing Rage, Ending Racism:

Beloved community is formed not by the eradication of difference but by its affirmation, by each of us claiming the identities and cultural legacies that shape who we are and how we live in the world.

Merritt and co-facilitator Lee Kay led attendees through a series of insightful exercises inviting people to reflect on their own cultural legacies and identities regarding race, religion or gender and then share learnings with a partner or the larger group.

Each attendee was assigned to a small group of five or six people consisting of mixed groups of young, old, white, black, or Latino people. Members were reminded to "assume positive intent," "listen, listen, listen," "accept each speaker's story as their own truth," and that "all relationships are intercultural."

Merritt was not raised Catholic but graduated from Cleveland's Ursuline College and then pursued a Master of Arts in psychology from Cleveland State University with certification in diversity management. She has more than 15 years of experience in organizational and leadership development.

But perhaps Merritt's most important qualification is that of an African-American wife and mother.

"I have a 21-year-old son living in the world," she said. "My son is in my heart as we engage in these conversations because for some of us, this is a truly life-or-death proposition."

Kay, who is also African-American, holds a degree in social work and is the founder and managing partner of Kay Coaching LLC, where she provides consulting and coaching services to grassroots community-based organizations. She credits her father, Louis A. Gleason, for her lifelong immersion in social justice and racial equality. Gleason ran the Campaign for Human Development in the Cleveland Diocese for many years.

"As Catholics," Kay reminded us, "we are leaders for justice."

After the first round addressing cultural legacies, the facilitators invited comments. Irene, an African-American woman from Holy Spirit Catholic Church, responded: "When I was born, nobody told me I was black. I never knew race was a 'black thing' until Martin Luther King came to town."

Trish from Ireland drew a laugh when she said her idea of race in Ireland was "putting a bet on the horses with a bookie."

Sister Michelle, a Sister of Notre Dame, related that as a white child in a military family, rank was more important than race. Her father's boss was black, and she had black friends. But when she moved to a conservative school near Washington, D.C., she was shocked: "They called the Civil War the war of northern aggression."

"The paradox of diversity," Merritt said, "is that we are unique and like no one else. We are each like some other people. We are each like all other people"

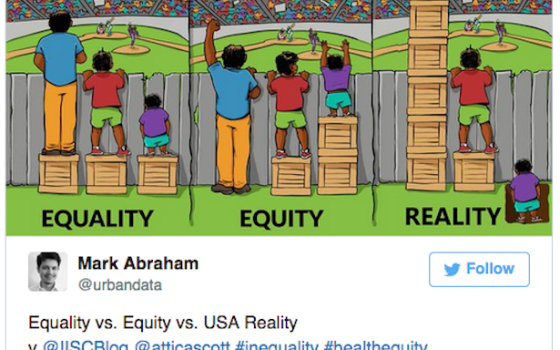

Some of the most animated exchanges were about a graphic about equality and equity that had gone viral on social media:

"Equity is giving different groups different resources so all groups can be on the same level," said Amelia Corrigan, a young white woman who had learned about the day from social media. Corrigan works as an academic adviser at Kent State and received diversity training for her work, which was where she learned about equity.

Tony Vento, who is white and works with young adults, wanted to know, "How did the person get all the way up on those boxes? It is a precarious position. What happens when he falls? Who gets hurt?"

Spiritual director Sr. Francis Therese Woznicki, a Sister of St. Joseph of the Third Order of St. Francis, observed that the person with the most boxes is "separated from the reality of the game that is uniting everyone else. This is true in our politics, also, where the dealmakers are cut off from suffering peoples."

One African-American woman named Gail said that "the guy in the middle can see no matter what. Even if he has some borderline security, he's comfortable and doesn't see the need to help."

Merritt asked, "How does this connect when we think about race? How did the little guy get in the hole? How did the guy with all the boxes get there?"

Structural racism exists, Merritt said, because there is a link between socioeconomics and race. For example, most white people are born into a system that privileges whiteness, and therefore, they have many more opportunities than people of color.

Merritt quoted economic studies that show it will take 243 years for the average black family to catch up with the average white family, presuming the socioeconomic status of the white family stays the same, which is unlikely.

After viewing a video clip that exemplified the unconscious bias of white privilege, Merritt asked what stood out.

Daniel, who is Latino, told of white friends who had urged him to self-identify as white rather than Hispanic when filling out a college application. He chose not to do so and graduated from an Ivy League school, although because of various obstacles, the three other Latinos in his class did not finish.

John Shields, the white co-convener of the Cleveland Diocese's racism committee, related that in 1968, despite his well-paying job as a metallurgical engineer, he was denied a credit card because he lived in a biracial neighborhood.

The final video clip addressed how to leverage white privilege to change a system rigged against people of color.

Merritt reminded the group that well-meaning white people need to "get past the blame, shame and guilt. White people are born into a system they didn't invent."

As an example of an unacknowledged system, she pointed to the privilege of right-handed people in the design of schoolroom desks and ringed notebooks. We must first acknowledge the system we are in before we can dismantle it, she said.

Christina Hannon, a young white woman, reflected, "I will never see white privilege playing out unless I choose to look at it and realize how many opportunities I have because of it."

"Our goal is to create a beloved community, and it will require a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives," Kay said in the final segment of the seminar. "How will you leverage your power to create a 'Beloved Community' in your neck of the woods?"

One important way is for white people to speak up when they notice people of color being held to a standard not demanded of whites. For example, a black parishioner from St. Aloysius parish said she had attended a play where she sat near women who happened to be white. She alone was singled out to display her ticket as proof of payment. None of the white women were required to show their tickets and, sadly, none objected to her unequal treatment.

Sr. Bela Mis, a Hispanic novice with the Sisters of the Precious Blood, found the day important because "we need to learn more and see a different perspective."

There is much fear among Hispanic Catholics over President Donald Trump's immigration ban, Mis said. She has a friend who is married to a U.S. citizen who went back to Central America a year ago to complete her permanent residency application. But her friend was then denied re-entry and has been separated from her son and her husband for over a year.

Two young African-American volunteers from a Southeast Seventh-day Adventist day camp found the seminar very helpful.

"It was inspiring," Chris Philpott said. "I learned something new: Violence doesn't give the answer. Black and white can come together, and we can join as one."

"Racism is taught, and everyone is affected," Margaret Johnson said. "So don't put it on anyone. We just need to come together. This seminar taught me a lot. It changed my idea of how I look at white culture."

[St. Joseph Sr. Christine Schenk served urban families for 18 years as a nurse midwife before co-founding FutureChurch, where she served for 23 years. She holds master's degrees in nursing and theology.]