Editor's note: From March 18 to 25, an interfaith group of about 75 people, including two dozen women religious, traveled to Honduras in a "reverse caravan" to see for themselves why tens of thousands of people have fled for their lives. Global Sisters Report is featuring columns from sisters who were part of the People of Faith Root Causes Delegation, which was sponsored by the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, SHARE El Salvador (Salvadoran Humanitarian Aid, Research and Education Foundation), the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas and the Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity. Read all of the columns.

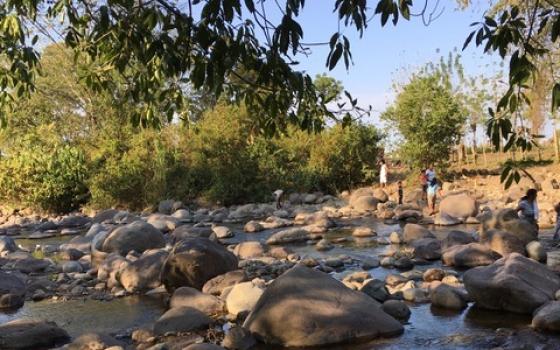

Caring for the earth, our common home, took on a new meaning for me on my recent "Root Causes of Migration" trip to Honduras. I was part of the interfaith delegation, and I requested to go with the group who travelled to Bajo Aguán. This is a beautiful rural area in the northern area of Honduras with lots of vegetation, mountains and trees, and clear flowing rivers sacred to the local people.

We hear so much in our news and social media about the caravans coming from Honduras. I was curious about what would make people flee from this lovely part of the country. I have a great appreciation for the earth, having grown up on a farm in West Cork in the south of Ireland, where I was close to the land, mountains and rivers. In Ireland we too have a long history of fighting for our land, with mass emigration in the past. Perhaps the struggles of the Irish attracted me to Honduras.

On our first morning in Bajo Aguán we met with local leaders and land defenders who shared some of the history of the region as well as their own involvement. They represented a powerful group of leaders who have a tremendous respect for their land and rivers.

Large tracts of territory in this region have been contested between groups of campesinos (small scale farmers) and the agro-industry businesses — mainly African palm oil. The farmers choose to resist what is happening despite the fear of arrest, kidnapping and death.

They told us that in the 1960s the Standard Fruits Company (now Dole Food Company), backed by the U.S. government, exploited the region for the banana industry. This type of agricultural production is not designed to satisfy human needs, but is designed for export. The local people go to bed hungry at night while everything that is produced is sent to other countries.

In the '70s, local small farmers created cooperative farms, which were successful until multinational corporations introduced the African palm oil plant throughout the region. The capital for this project came from Canada, the World Bank and other countries and institutions.

According to local leaders, there are now an estimated 70,000 hectares of cultivated African palm plants in this area, which consume an estimated 200 million liters of water daily. The normal production of agrarian food is disappearing; before this happened, the local campesinos worked the land to provide food to feed their families and to generate an income.

Jesuit Fr. Ismael Moreno Coto (popularly known as Padre Melo) at Radio Progresso and the local leaders explained that this has forcibly displaced the local people, destroyed the social fabric of the community and created a lot of conflict in the region.

Another threatened region is the mountainous area, where extractive mining and hydroelectric projects are impacting the rivers and threatening the whole environmental structure of the region.

This extractive model creates a very deep crisis because of the irreversible environmental impact it has on the region, destroying the fragile ecosystems around the river.

Two years after the mining company started, the people were alarmed when one morning they went to the river and the water was brown; they were no longer able to use the river for their normal uses of drinking, cooking, bathing and washing their clothes. The people began fighting back to defend their land and rivers. There were violent protests against government forces and the local security hired by the mining company.

Women can't go to their own homes to sleep at night because they are under death threats. However, the people say they are willing to die for their land and their rivers they hold so sacred.

They have been inspired by Berta Cáceres, who cofounded the National Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH) in 1993. She devoted 10 years to campaigning to stop the construction of the Agua Zarca dam on the Gualcarque River. After years of protests and campaigning, the Chinese partner of the Honduras company and the international corporation withdrew their support for the Agua Zarca dam in 2013. Berta was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2015. A year later, on March 2, 2016, Berta was murdered in her own home by hired assassins.

So the control of the land and rivers by the wealthy and their corporate interests has created an environment of social instability and forced the expulsion of the people. This is what creates the caravans.

It is important that we join the movement to lobby our legislators and to back HR. 1945, the Berta Cáceres Human Rights in Honduras Act, reintroduced by Rep. Hank Johnson. The bill will work to ensure that the Honduran government, military and police cannot commit crimes or acts of violence against the Honduran people with impunity.

What I witnessed in Honduras moved me out of my comfort zone and motivated me to be more of an advocate. I will begin by studying the issues in a different light. The Hondurans' care for the earth and their rivers made me realize how naïve I am with regards to care for our common home. Who knows? Maybe I will start protesting multinational companies and lobbying legislators.

[Margaret Farrell is a member of the Religious Sisters of Charity, originally from County Cork in Ireland. She has ministered in Ireland and England as a prison chaplain, in a domestic violence shelter and in outreach to the homeless. For the past 20 years she has been living and working in California, and is currently working as the spiritual ministry coordinator at Covenant House California.]