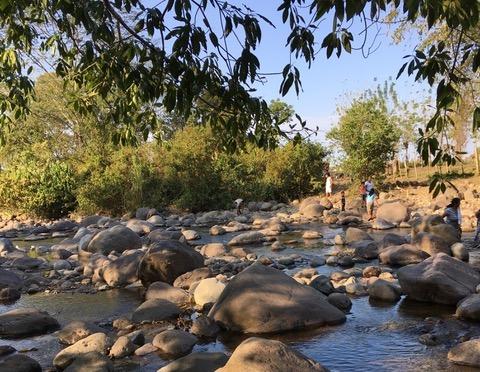

The Rio Aguán is one of the rivers under threat at the moment by a mining company. Some of the local people were recently arrested for protesting in defense of the river. They were released after 12 days in Tamara prison. (Margaret Farrell)

Alone or with a partner:

- Develop a list of three positive reasons and three negative reasons why people might move from their homes or their homelands.

- Describe feelings people experience when they have to move.

People migrate to new countries for many reasons. We often hear stories of people seeking new opportunities in the United States and other countries, but increasing numbers of people are leaving their homelands to escape violence, oppression and injustice. Rather than simply worrying about immigration or making bad assumptions, many people – including sisters – decided to explore the source of a problem.

Our common home in Honduras

Editor's note: From March 18 to 25, an interfaith group of about 75 people, including two dozen women religious, traveled to Honduras in a "reverse caravan" to see for themselves why tens of thousands of people have fled for their lives. Global Sisters Report is featuring columns from sisters who were part of the People of Faith Root Causes Delegation, which was sponsored by the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, SHARE El Salvador (Salvadoran Humanitarian Aid, Research and Education Foundation), the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas and the Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity. Read all of the columns.

Caring for the earth, our common home, took on a new meaning for me on my recent "Root Causes of Migration" trip to Honduras. I was part of the interfaith delegation, and I requested to go with the group who travelled to Bajo Aguán. This is a beautiful rural area in the northern area of Honduras with lots of vegetation, mountains and clear rivers sacred to the local people.

We hear so much in our news and social media about the caravans coming from Honduras. I was curious about what would make people flee from this lovely part of the country. I have a great appreciation for the earth, having grown up on a farm in West Cork in the south of Ireland, where I was close to the land, mountains and rivers. In Ireland we too have a long history of fighting for our land, with mass emigration in the past. Perhaps the struggles of the Irish attracted me to Honduras.

On our first morning in Bajo Aguán we met with local leaders and land defenders who shared some of the history of the region as well as their own involvement. They represented a powerful group of leaders who have a tremendous respect for their land and rivers.

Large tracts of territory in this region have been contested between groups of campesinos (small scale farmers) and the agro-industry businesses — mainly African palm oil. The farmers choose to resist what is happening despite the fear of arrest, kidnapping and death.

They told us that in the 1960s the Standard Fruits Company (now Dole Food Company), backed by the U.S. government, exploited the region for the banana industry. This type of agricultural production is not designed to satisfy human needs, but is designed for export. The local people go to bed hungry at night while everything that is produced is sent to other countries.

In the '70s, local small farmers created cooperative farms, which were successful until multinational corporations introduced the African palm oil plant throughout the region. The capital for this project came from Canada, the World Bank and other countries and institutions.

According to local leaders, there are now an estimated 70,000 hectares of cultivated African palm plants in this area, which consume an estimated 200 million liters of water daily. The normal production of food is disappearing; before this happened, the local campesinos worked the land to provide food to feed their families and to generate an income.

Jesuit Fr. Ismael Moreno Coto (known as Padre Melo) at Radio Progresso and the local leaders explained that this has forcibly displaced the local people, destroyed the social fabric of the community and created a lot of conflict in the region.

Another threatened region is the mountainous area, where extractive mining and hydroelectric projects are impacting the rivers and threatening the whole environmental structure of the region.

This extractive model creates a very deep crisis because of the irreversible environmental impact it has on the region, destroying the fragile ecosystems around the river.

Two years after the mining company started, the people were alarmed when one morning they went to the river and the water was brown; they were no longer able to use the river for drinking, cooking, bathing and washing their clothes. The people began fighting back to defend their land and rivers. There were violent protests against government forces and the local security hired by the mining company.

Women can't go to their own homes to sleep at night because they are under death threats. However, the people say they are willing to die for their land and their rivers they hold so sacred.

They have been inspired by Berta Cáceres, who cofounded the National Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH) in 1993. She devoted 10 years to campaigning to stop the construction of the Agua Zarca dam on the Gualcarque River. After campaigns and protests went on for years, the Chinese partner of the Honduras company and the international corporation withdrew their support for the dam in 2013. Cáceres was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2015. A year later, on March 2, 2016, hired assassins murdered her in her home.

So the control of the land and rivers by the wealthy and their corporate interests has created an environment of social instability and forced the expulsion of the people. This is what creates the caravans.

It is important that we join the movement to lobby our legislators and to back HR. 1945, the Berta Cáceres Human Rights in Honduras Act, reintroduced by Rep. Hank Johnson. The bill will work to ensure that the Honduran government, military and police cannot commit crimes or acts of violence against the Honduran people with impunity.

What I witnessed in Honduras moved me out of my comfort zone and motivated me to be more of an advocate. I will begin by studying the issues in a different light. The Hondurans' care for the earth and their rivers made me realize how naïve I am with regards to care for our common home. Who knows? Maybe I will start protesting multinational companies and lobbying legislators.

Alone or with a partner, discuss the following:

- Sr. Margaret observes the destruction of ecosystems and the unraveling of the social fabric in the community. How would you and your family respond if similar situations were happening around you?

- Some Hondurans have fled their homeland because of what has happened to its natural resources. Others have chosen to fight and die to protect the land and rivers. As an outsider, what other options can you envision beyond these extreme choices?

Job was a good man who lived a holy life, but horrible things happened to him. Despite that, he accepted his suffering and remained faithful to God. That's not to say, however, that he was naïve about evil in the world. Among his observations about the bad things that other people did, he said:

"People remove landmarks;

they steal herds and pasture them.

The donkeys of orphans they drive away;

they take the widow’s ox for a pledge.

They force the needy off the road;

all the poor of the land are driven into hiding."

- What conditions lead people to exploit other people and rob them of their land and other possessions?

- Some people ask "why does God let bad things happen to good people?" It’s an honest question but not a productive one. Sometimes even praying doesn't seem to be enough. How can the people of faith help keep farmers on their land and protect precious natural resources like water and the tropical rainforests?

Pope Francis recognizes the plight of people who leave their homelands because of harm to the environment. In his recent encyclical, he shares concern for people like those Sr. Margaret Farrell writes about:

"There has been a tragic rise in the number of migrants seeking to flee from the growing poverty caused by environmental degradation. They are not recognized by international conventions as refugees; they bear the loss of the lives they have left behind, without enjoying any legal protection whatsoever. Sadly, there is widespread indifference to such suffering, which is even now taking place throughout our world. Our lack of response to these tragedies involving our brothers and sisters points to the loss of that sense of responsibility for our fellow men and women upon which all civil society is founded."

"Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home"

- Like Pope Francis, Sr. Margaret refers to the earth as "our common home." What does she have in common with the Honduran people she visited?

- What can be done to overcome the world’s indifference to their suffering?

For more than a decade, the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas have been responding to human rights abuses in Honduras. Learn more here about the sisters’ efforts.

Discover more about the stories of newcomers in your community. Work with your parish’s social action committee or your diocese’s social justice office to connect with immigrants and refugees. Invite them to share their stories with your class. Ask:

- Why did they leave their homeland?

- Did environmental concerns affect their decision?

- What hardships did they endure to get here?

- If things had been different, would they still have left?

Loving God, we praise you for the blessings of the fields and streams, the plants and animals and all good things you have created.

We also thank you for our hearts and minds. Renew and refresh these gifts, Lord, so that we might open them to ways to live in harmony with nature and with each other.

Bless those who care for the land and water, and guide the steps of those who travel when hope seems lost.

Amen.

Tell us what you think about this resource, or give us ideas for other resources you'd like to see, by contacting us at [email protected]