Although hundreds of miles separate them, two sisters in the neighboring Central American countries of Guatemala and Honduras see the same kinds of children.

The boys and girls they watch create their own chaos on bustling playgrounds, dodging behind poles in a tactics-driven game of hide-and-seek. Other children sit at tables in palely lit classrooms sharing homework with one another as they wait for class to begin. Still others stand in line for their daily dose of HIV antibiotics.

These children live in orphanages for boys and girls born HIV positive. They are among the 3,000 HIV-positive children age 14 and younger in the two countries, according to UNAID.

Some of the orphans lost their parents to AIDS, or their families abandoned them. In other instances, the courts removed children from homes so dysfunctional that parents lacked the discipline to give their children the HIV antibiotics they needed to survive.

Unwanted, parentless or removed from their homes, the children forge new families in the two orphanages where the sisters work. For most of their young lives, the children have relied on the care of nuns who never had children of their own but who raise these boys and girls with love, worry and pride.

But beneath the sisters' devotion lies uncertainty. The orphanages, with high, cinder-block walls, stand as havens from the rejection the children suffered from the outside world. They come here as young as infants and sometimes stay until they are as old as 20. However, they can't stay longer than that. They will need to leave. Leave the only people they know to have loved them, leave the only place they have known as home. Leave to forge new lives in a world where many people view them as pariahs.

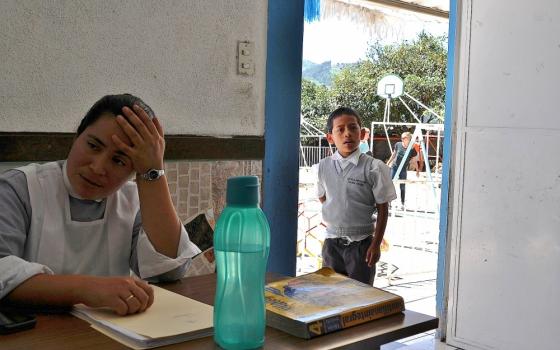

The stern face of Sr. Modesta Cuma, the principal at the orphanage Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello in Sumpango, Guatemala, quivers and dampens with tears as she contemplates the children's futures. A sister with the order of Small Apostles of Redemption, she knows nothing certain awaits them.

"We get very stressed when we don't know what will happen to the children when they leave here," she said from the front stoop outside her office at Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello. "This year, we will lose four. Of course, we all feel like mothers. It is so sad to see them leave. We hope God helps them go through this difficult time."

In the Honduran orphanage, Hogar Casa Corazón de la Misericordia in San Pedro Sula, Mercy Sr. Sandra Hernandez has similar worries made worse by fears of gang violence.

"When the children get older, gangs approach them to join them," Hernandez said. "That is why we have razor wire from every angle on our walls, to stop them from trying to get in, particularly in dorms where girls live. One girl fell in love with a gang member. We can't say, 'Don't be in touch with him.' She might get angry and leave with him. I am like a parent. My only concern is their well-being."

___

Tourists who visit the historic town of Antigua, Guatemala, minutes outside Sumpango, likely never see Hogar Madre Anna Vitiello, which has been here since 2005. The orphanage stands outside of town off a rocky dirt road lined with small, ruined storefronts of square buildings with gaping holes in their walls.

The iron gate of the orphanage opens only for staff and volunteers. Inside the compound, white buildings filmed with evaporating dew shine in the morning sun. Children run after one another in the large courtyard, their voices echoing off the walls, behaving as if the sisters had not roused them, sleepy-eyed, at 5:30 a.m.

The orphanage has capacity for 100 children. When boys reach the age of 12, the sisters try to transfer them to orphanages for older boys, said Cuma, 51, because boys "are difficult to control when they reach adolescence."

Girls can remain at the orphanage until 15, when they, too, are referred to programs for older children. But more often than not, other programs don't have space for additional children. As a consequence, the children remain at the orphanage until 18 and even sometimes 20. Then, Cuma said, they must be moved on.

Heidi Herrera, 15, is one of four children who will leave the orphanage by the end of this year. She is the oldest child here, a kind of big sister to the other children. When doctors informed her mother of Heidi's HIV diagnosis, she locked Heidi in a cage inside their house. The girl's two older siblings reported their mother to the police, and the courts referred her to the orphanage. Now, these many years later, her siblings have offered to take her in.

"She is very smart," Cuma said of Heidi. "She has a good understanding of her disease. Her siblings are responsible and working, and her paternal grandmother will also help."

Heidi, however, feels less than certain about her future.

"I am aware the time to leave here is coming," she said. "I am worried. What kind of home will I have?"

Across the courtyard, Sr. Flor Ramirez, 31, prepared to give her mid-morning reading class to about 15 8-year-olds. She said her primary job is to make the children understand that they should be loved no less than other children. The children, she said, fear rejection. Ramirez tells them that they will outgrow these worries, that when they get older they will know how to manage the disease and the reaction people have to it.

"If the children leave for a family, I am glad," Ramirez said. "If they leave for another kind of home, like another orphanage, I am concerned. I hope they will be treated with affection. I know one girl who left here four years ago. She was 15. She didn't take her medication, and she died."

One of the students in Ramirez's class one hot July afternoon was Gustavo Ramirez, 11 (no relation to the sister). He said the sisters at the orphanage told him he was brought here when he was 3 months old. No one has explained to him why, other than he was sick with HIV. An uncle, brother and his grandparents visit him twice a year. Sometimes they call him, and when they do, he asks them when they will see him again. "Someday," they tell him.

"I am happy because they called and we talked on the phone and they remembered me," Gustavo said. "I dream about my family. I dream they will take me back when I leave here. I dream about going home and spending Christmas with them. In my dream, I see my family and everyone is happy."

___

Hogar Casa Corazón de la Misericordia opened in 1995. It had always been an ambition of Hernandez's to help children even before she joined the Sisters of Mercy. Her parents worked all day, and she was often left home alone as a child. Wouldn't it be nice, she thought at the time, to gather all the lonely children in the world in one place?

When the HIV/AIDS epidemic broke out in Honduras in the mid-1980s, she and another Sister of Mercy opened the orphanage, providing space for 25 children, which remains the capacity today.

Seventeen children died in the first few years. They came to the orphanage so sick that the sisters could do little for them other than make them as comfortable as possible. The municipality gave them space in the public cemetery where other people are buried as "John Doe."

"One boy, Angel, was just 9," Hernandez, 48, said. "He was afraid of dying. He had a frightened expression on his face. We massaged his hands and sang to him and told him, 'Don't worry. Let yourself go.' To this day, everyone remembers him. At every gathering, one of us thinks about him and all these feelings come back."

The orphanage accepts children of all ages. They can stay at the orphanage until they reach 18, but if they continue with their education, they can stay until they graduate college.

From the day the children arrive, Hernandez said, the sisters and volunteers speak to them about HIV. The talks vary depending on the age of each child, but the message remains the same: The children need to understand that they must take medication for the rest of their lives.

"We talk to them in a straightforward, loving way, and the children respond well," Hernandez said. "The children can stay as long as they want, providing they attend school. Eventually, they have to leave, but they are never forced."

Hernandez said she prefers to take in newborns because they don't carry the sense of grief that older children have. Newborns can be taught everything "from the start of their lives," she said. "They are a blank slate."

Older children, however, bring a burden of loss with them into the orphanage. Their parents have died. Family members rarely visit them. They no longer live in the neighborhoods where they were born. Hernandez and the other sisters have to confront these children's grief until they accept their new home.

Unlike the Guatemalan orphanage, the Honduran orphanage does not have a school on site. The boys and girls there attend public schools, where some activities remind them that their mothers and fathers have died or abandoned them. A teacher might say, "Make a card for Mother's Day," and the orphans find themselves confronted by their parentless status.

To address this problem, Hernandez hired Maria Laura Donaire shortly after the orphanage opened for the sole purpose of serving as a mother of the orphans. Donaire, a laywoman, attends all school and sporting events involving the children, helps them with their homework, takes them shopping and performs other tasks any mother would do.

"My job is to literally be the mother of these children," Donaire, 62, said. "Sometimes, I am challenged. One time, when we went out to buy fruit, one girl said, 'Momma, buy us apples and bananas.' The vendor said, 'These are all your children?' 'Yes,' I said. 'All of them.' I have a special place in my heart for all of the children. All of them are my favorite."

Donaire gave two orphans without birth certificates, Kenia and Johnny, her last name.

"I went to my hometown and registered them as my children so they would have an identity," Donaire said. "I was friends with the mayor and I explained the situation and he approved the paperwork. They know I am not their biological mother, but here I am, their mother."

Kenia, now 20, a university student and a volunteer with the National Forum on AIDS in Tegucigalpa, said she will continue to live at the orphanage until she graduates. Donaire told her she has lived here since she was 7 months old. Her mother had seven daughters. Kenia was the youngest.

"I am told that my mother was very brave and hard-working," Kenia said. "She was a maid and cleaned clothes. In the end, she was a sex worker to earn money to support us. She needed surgery, so she brought me here to stay while she was in the hospital. I never heard from her again. She was supposed to pick me up, but didn't."

Kenia said she has long since accepted her HIV diagnosis.

"I have been dealing with this my entire life," she said. "In school, some children discriminated against me. They asked me a lot of questions. Instead of getting angry, Momma Laura told me to educate them. I went back and told them, 'No matter who you are or what your condition is, you'll eventually die. Rather than be afraid of me, live your life to the fullest.' "

Violence remains an ongoing concern for the orphanage. San Pedro Sula is considered the murder capital of the world, where 171 people were killed for every 100,000 residents in 2015.

"The children know about violence," Hernandez said. "They come home after school and say, 'We saw a dead guy. We saw someone who was shot.' Or they hear from their friends about someone who was found dead. It is the talk of the day."

Hernandez also knows about violence. Her younger brother was shot and left dead on the street last year. Her sister was kidnapped this year. Hernandez has no idea what has happened to her. She is now raising her sister's 6-year-old daughter at the orphanage.

"We close all the gates, every possible way for someone to break in here," she said. "All the dormitories are connected so no one has to go outside. So far, the gangs have never approached the orphanage. Maybe they respect us. Maybe they discriminate against us because they think they'll get AIDS."

The children say they feel secure in the sanctuary the orphanage provides them. The dangers of the outside world have yet to penetrate here. Within this enclosure, they behave like other children: playing, procrastinating on their homework and showing off to one another. But unlike other children, they wonder about the mysteries of their lives, the combination of factors that brought them to the orphanage.

"I've not been told about my mother other than she died," said Dulce Rodriguez, 11, who has been at the orphanage since she was 4. She was told she was too sick for her family to care for her. "I know her name: Gladys Maribel Castillo Hernandez. I know that much about her."

Dulce said her grandmother raised her.

"She brought me here. She told me to feel as I do at home. My first day here was sad. I could not see my grandmother. After the first day, I was OK. My grandmother visits two times a year. She lives far away."

Dulce hopes to be an actress. She likes to be in plays and enjoys making people laugh.

"Please don't be threatened by me," Dulce said she has told people who learn about her HIV status. "I am not going to harm you in any way."

___

At the end of each day, Cuma and Hernandez watch the children play before it is time for dinner, evening prayers and bed. They run around, free for the moment of any discipline and concerns. People who visit both orphanages have told the sisters that they cannot believe the children are sick.

Cuma's faith has taught her to forgive those people who don't ask for forgiveness. Those people who are irresponsible parents, those people who would reject and ostracize a sick child, those people who would take advantage and harm them.

"You can never give an abandoned child all that they need," she said. "But you can give your best to every one of them every day."

Hernandez embraces her work with gratitude.

"It is a privilege to be with them," she said of the children. "They give me more than I give them. My brother was killed and my sister has disappeared, yet through all this I feel happy and loved by these children. They are God's grace. It is unfortunate so many people in the world don't see them that way."

[J. Malcolm Garcia is a freelance writer and author of The Khaarijee: A Chronicle of Friendship and War in Kabul, What Wars Leave Behind: The Faceless and the Forgotten. He is a recipient of the Studs Terkel Prize for writing about the working classes and the Sigma Delta Chi Award for excellence in journalism.]