Ku Klux Klan parade, Washington, D.C., Sept. 13, 1926, during a period when the group's popularity was surging across the United States (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

When nativist powers like the Ku Klux Klan and the state's own governor confronted the religious community of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary in 1920s Oregon, it was a clash of historic proportions.

At stake? Something relatively commonplace today — the right of parents to decide where their children could be educated.

At the time, said Sr. Carol Higgins, a member of Holy Names of Jesus and Mary who has studied the era, Catholics in Oregon made up less than 10% of the population.

In the early years of the 20th century, the Ku Klux Klan, a jingoistic and racist organization founded in the South to reverse Reconstruction policies after the Civil War, was surging in popularity across the United States. Its influence stretched well beyond the former states of the Confederacy. In Oregon at that time, "the Klan had more KKK members than any other state in the union," she said.

"It's kind of the same rallying cry we're hearing today," she said. " 'We want America to look like we look and think the way we think. Diversity is not a good thing.' And so, they were going to make it happen by educating children."

Advertisement

Though there weren't many Catholics in 1920s Oregon, there were even fewer Black people. That's due in part to the "exclusion laws" on the books, meant to keep Blacks, Jews, Japanese and other immigrants from owning land, said Higgins. The governor at the time, Walter Pierce, though progressive on many issues, like the 19th century abolitionists, had nativist sympathies and the backing of the Klan when he became governor in 1922.

That was the year Oregon voters passed the Compulsory Public Education Act, which was just what it sounded like, sparking a backlash not only from Catholics but also from other denominations and private academies. Though the bill didn't mention Catholic schools, said Higgins, they were clearly the target. "The Klan saw the measure as a way to Americanize Catholic children and make sure that they didn't receive an anti-Protestant message." (The KKK also backed a similar bill in Washington state in 1924, which sparked a lot of local opposition and was defeated.)

A year later, said Higgins, the legislature passed the Oregon School Garb Bill, which made it unlawful for public school teachers to wear religious clothing while teaching. "So again, it was directly targeting the sisters who were teaching in the public schools, providing the service because there weren't enough teachers," said Higgins.

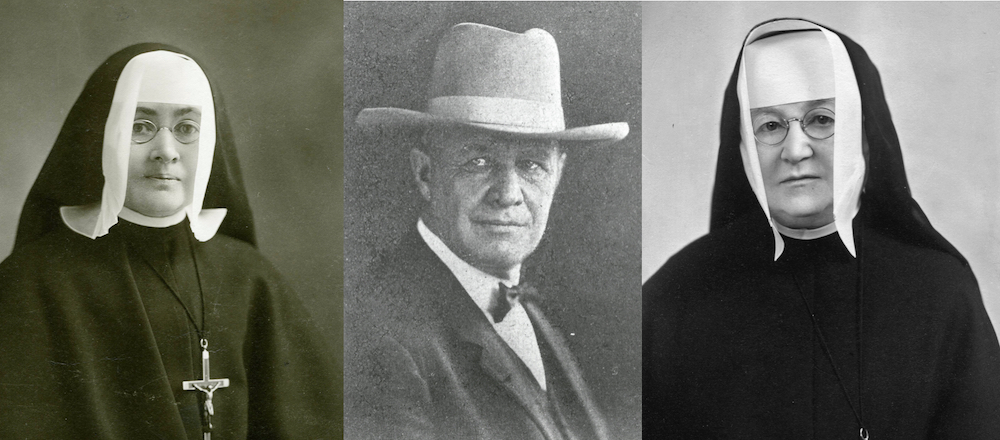

Left: Sr. Mary Flavia Dunn was Oregon provincial of the Society of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary from 1911 to 1920 and had occasions on which she confronted the Ku Klux Klan, according to the order's history. (Courtesy of the Sisters of the Holy Name of Jesus and Mary, U.S.-Ontario Province archives); Center: A progressive in many other respects, Gov. Walter Pierce of Oregon was also a nativist, backing the Klan and the anti-Catholic Compulsory School Act, which targeted parochial schools. (Oregon Historical Society Archives); Right: Mother Alphonsus Mary Daly was Oregon provincial of the Society of the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary from 1920 to 1929. In reaction to the state move to mandate public education for all Oregon children, the order sued Gov. Walter Pierce and other state officials for the right of families to choose where their children would be educated. (Courtesy of the Sisters of the Holy Name of Jesus and Mary, U.S.-Ontario Province archives)

Because the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary had established schools in various parts of the state, then-Archbishop of Portland, Alexander Christie, asked the women, joined by a military academy, to sue for an injunction against the law. Instead of focusing on the question of religious liberty, the lawsuit centered on the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. The writers of the brief argued that the law would close Catholic schools and thus deprive sisters of their property without due process.

In 1924, a federal district court agreed, granting the injunction. And in June of the next year (Oregon had appealed the decision), so did the United States Supreme Court in the case that has become known as Pierce vs. Society of Sisters.

"Our joy is unbounded — it is as if the very floodgates of Heaven had opened and poured out upon the length and breadth of our own United States the refreshing waters of renewal of spirit. The God-sent verdict passed from one expectant heart to another with lightning speed and on the instant more than ten thousand times ten thousand voices sang through the very vaults of Heaven with a jubilant thanksgiving which then but intoned the eternal hymn," wrote a sister that day in the Chronicles kept by the order at the convent in Marylhurst, Oregon. She referenced their late Archbishop Christie, who had died before the Supreme Court decision, and proclaimed "that none would know the secret of the unparalleled victory before he did."

In the long run, the case established that parents, the primary educators of their children, had a right to have them educated any way they wish, said Higgins. Almost a 100 years later, "families can have their children in public schools, private schools, Catholic schools, home schools and online schools. The freedom to make any of those decisions comes directly from this court case."