Destroyed homes and businesses on Pine Island, Florida, are seen from a U.S. Army National Guard Blackhawk helicopter Oct. 1, 2022, after Hurricane Ian caused widespread destruction. (CNS/Reuters/Kevin Fogarty)

Insurance costs for religious communities — and everyone else — are going to rise dramatically.

Insurance expert Stephen Waldorf told attendees at the Resource Center for Religious Institutes' annual conference in September that congregations are facing a triple whammy that will make insurance not only far more expensive, but in some cases unavailable. And all of it is driven by climate change.

Waldorf is managing partner at Waldorf Risk Solutions, a firm in Huntington, New York, that specializes in insuring religious organizations and other nonprofits. He enumerated three looming factors in the insurance industry:

- The cost of reinsurance — insurance policies that insurance companies buy to mitigate their losses — is exploding.

- Property has been undervalued and insurers are trying to catch up, meaning costs would rise even if rates do not, which they will.

- The scope and scale of natural disasters has soared, leading to massive losses by insurance companies.

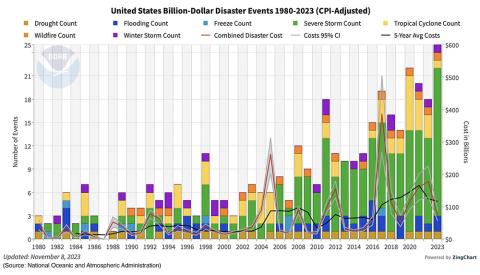

According to statistics kept by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the cost of natural disasters that caused at least $1 billion in damage increased by more than 50% from the 1980s to the 1990s, then nearly doubled again in the 2000s, and went up another 60% between 2010 and 2019, when the total for the decade reached nearly $1 trillion.

In 2017, the total cost of disasters such as drought, floods, freezes, severe storms, hurricanes and winter storms hit a peak of $387 billion — more than the total cost of disasters for the entire decade of the 1990s, even after adjusted for inflation.

"The problem is these storms are getting bigger and stronger than anyone ever anticipated," Waldorf said. And it's not just major disasters such as hurricanes. "Thunderstorms are bigger, they're stronger, they're more dangerous than anyone can remember."

Hurricane Ian in 2022 caused $90 billion in damage, he said, requiring $60 billion in insurance payouts. That caused reinsurance companies to get out of the market, and those that were left raised rates dramatically.

Many reinsurance companies are global, so they are also affected by disasters around the world, such as the February earthquake in Turkey and Syria, which killed at least 56,000 people and caused more than $34 billion in damage.

Waldorf said that when reinsurance companies left the market in Florida, insurance companies not only raised their premiums to cover the higher costs of reinsurance, but became much more careful about which risks they are willing to take.

"It's not just that the cost of insurance is getting more expensive, but they're getting more selective," Waldorf said.

The cost of insurance has risen so high in places targeted by disasters such as hurricanes that people simply cannot afford it.

"There are people in Florida saying, 'I'm not going to buy it,' " Waldorf said. "Then a storm comes in and you're left with just a slab and you can't rebuild because you didn't have insurance."

Waldorf is an insurance broker, meaning he helps clients find and purchase insurance from several different companies.

"I used to have 20 different markets. I'm now down to five," he said. "And those five that are left, they're very restrictive and very expensive."

Advertisement

And even if, by some miracle, rates didn't go up, the cost will still likely increase because of rising property values. Insurance companies do not want to base their premiums on one value, only to have a claim and have to pay out much more because the value increased.

"The past three years, there's been a big concern on valuations," Waldorf said. "They're arguing properties are grossly undervalued and saying that, nationally, on average values should be up 13%."

And things are only expected to get worse.

"The average of catastrophic losses has more than doubled ... and we know what's driving it," Waldorf said.

According to United Nations reports released ahead of the COP28 climate summit, greenhouse gas emissions are not falling, but increasing, and countries are planning to produce more than double the fossil fuels in 2030 than what might limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, which is the limit scientists say will keep us from catastrophic effects of climate change, Reuters reported. Instead, the reports found the planet is on track to see a 3 degrees Celsius increase in temperatures.

"I hate to bring you this kind of news, but I don't see it getting better," Waldorf said. "We're going to see increases in the frequency and severity of disasters in places we've never seen it before."

He said global sea-level rise could reach 20 feet, and noted that the average elevation of Miami is only 6 feet above sea level.

Meanwhile, melting permafrost in the Arctic is releasing large amounts of methane, which is an even more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, and it is also freeing viruses and bacteria humans have not seen in centuries and may not be immune to.

All of which means higher insurance costs for religious communities that may already be struggling financially. The National Religious Retirement Office says that of 506 congregations that provided data, only 31 are adequately funded for retirement. A 2016 study projected that by 2034, religious institutes will be short a combined $9.8 billion to care for their older members.

"It concerns me more than it ever has," Waldorf said. "The cost of insurance is now rivaling the cost of payroll."