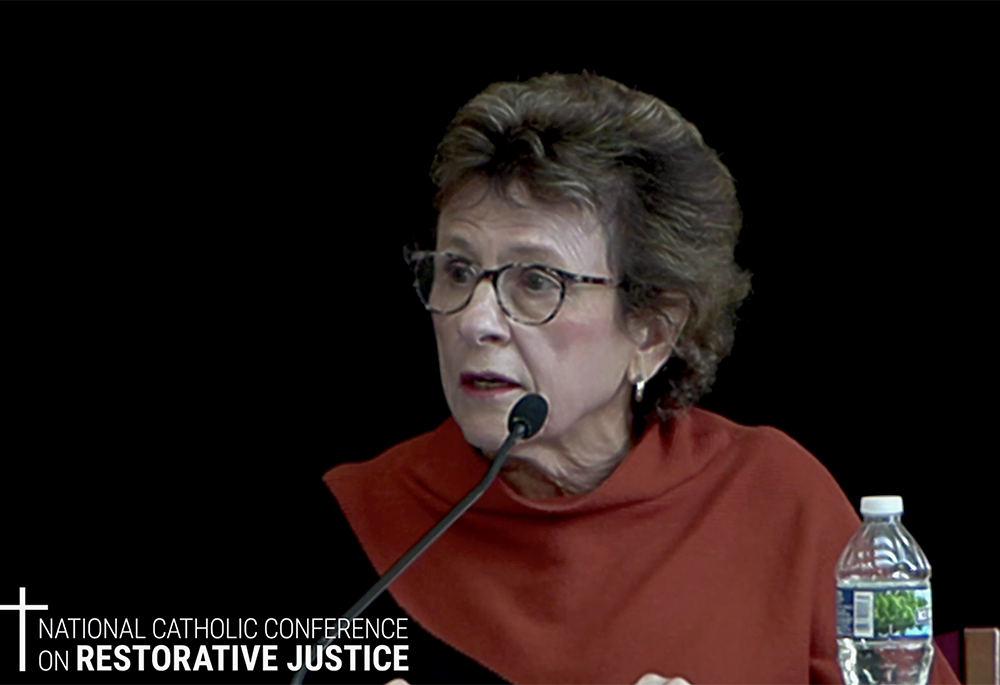

Barbara Thorp, a social worker and the former director of Office of Pastoral Support and Child Protection for the Archdiocese of Boston, speaks Oct. 6 at the National Catholic Conference on Restorative Justice in Minneapolis. (NCR screenshot)

Despite more than two decades of efforts to transform the Catholic Church to bring justice to sexual abuse victims and ensure widespread abuse and its cover-up do not happen again, there is much to be done, advocates say.

Barbara Thorp, a social worker and the former director of Office of Pastoral Support and Child Protection for the Boston Archdiocese, told the National Catholic Conference on Restorative Justice Oct. 6 that while great strides have been made in some areas, shocking examples of failure continue to arise.

"The resistance to the necessary institutional changes to ensure justice are in many places not only glacial, but frozen," Thorp told several hundred attendees at the conference, which was held Oct. 5-7 at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis. "Jesus said, 'You are the light of the world,' but in practice, it's more like a 10-watt bulb flickering than the penetrating light of Christ."

She cited the case of Fr. Marko Ivan Rupnik, who was allegedly protected and embraced despite three decades of accusations that he had sexually, spiritually and psychologically abused women, then pointed to a Sept. 27 statement by the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors.

"I've read many statements over the years, but this one was something," Thorp said. "One sentence struck me like a lightning bolt: 'No one should have to beg for justice in the church.' I'll repeat it: 'No one should have to beg for justice in the church.' "

Advertisement

But that is exactly what happens when victims are not believed, are shunned or silenced, or wait years — and sometimes decades — for any justice at all, she said, giving the example of a man from Boston who waited 20 years for the church to finally find his abuser guilty, only to have the priest die at age 90 a few months later.

Panelist Juan Carlos Cruz, a member of the Pontifical Commission and himself a survivor of sexual abuse by a priest in his native Chile, said survivors of alleged abuse by Bishop Carlos Filipe Ximenes Belo of Dili are being silenced.

"These people in East Timor are threatened with death if they talk about their bishop," Cruz said. "It is profoundly embarrassing to me that these things have gone on."

Juan Carlos Cruz, a member of the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors and a survivor of sexual abuse by a priest in his native Chile, speaks Oct. 6 at the National Catholic Conference on Restorative Justice in Minneapolis. (NCR screenshot)

The situation is especially striking when there are examples of not just justice, but restorative justice taking place, Thorp and other panelists said. They pointed to work in the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis, which sponsored the panel and whose archbishop, Bernard Hebda, was a panelist. Hebda took over the archdiocese after it was roiled by hundreds of sexual abuse cases, decades of cover-ups, and criminal charges against the archdiocese itself.

Hebda said he has met with dozens of abuse survivors and will meet with any more that ask, and that other sessions during the conference reminded him he must also meet with survivors of Native American boarding schools, many of which were run by Catholic orders of nuns and priests. The important thing, he said, is to really listen.

"I've been with some people who are so alienated from the church and rightfully angry. … But those who have been harmed are the ones who need to lead those conversations," he said. "That can be difficult, because the initial instinct for me is to do something to help, to fix something."

But truly listening to survivors can bring transformation.

Archbishop Bernard Hebda of St. Paul and Minneapolis speaks Oct. 6 at the National Catholic Conference on Restorative Justice in Minneapolis. (NCR screenshot)

"It's amazing that people who have been so negatively impacted by the church are willing to be our allies to bring the church to where it needs to be," Hebda said. "I can't imagine what my ministry would be without people willing to trust me with their stories."

He said an important change the archdiocese made was to appoint an independent ombudsman for accountability.

"They're available to someone who feels they haven't been heard," Hebda said. "If [survivors] don't feel I'm doing my job well … there's an outside person to listen to them and walk with them."

St. Joseph Sr. Helen Prejean, author of Dead Man Walking and an anti-death penalty advocate, speaks Oct. 5 at the National Catholic Conference on Restorative Justice in Minneapolis. (NCR screenshot)

In an Oct. 5 session on finding restorative justice in the current environment, St. Joseph Sr. Helen Prejean said state executions are held in secret because people would never allow the death penalty if they saw it in action. Prejean, author of Dead Man Walking and an anti-death penalty advocate, has accompanied six people during their executions.

"My eyes saw what most of us in this society will never see because it is kept secret," Prejean said. "Restorative justice is the opposite of secrecy."

Other sessions at the conference centered on racism, boarding schools and how restorative justice can eventually lead to reconciliation. Restorative justice, many participants said, is not simply forgiving the offender, but embracing the righteous anger of the offended and finding a way to right relationships.