Catholic sisters provide healing, care, hope, courage and education in Africa and improve the quality of life for those suffering hardships in rural communities. They emulate Christ’s mission to “bring good news to the poor, proclaim liberty to captives, recovery of sight to the blind and proclaim the Lord’s year of favor” (Lk 4:18).

A visit to the Maria Adelaide Center threw into sharp relief the shared story of countless rural girls who are liberated from cultural practices that hold them captive bodily, psychologically and socially. It is a story of freedom that also rekindles in girls the hope of acquiring an education to live out their long-cherished dreams. For Sr. Carol Kimani, director of the center, there is no better way to bring the message of Christ to uneducated girls in Ewaso Kedong than providing a safe haven where their dreams and hopes are nurtured.

The Maria Adelaide Center is among 30 ministries I visited recently that are run by Catholic sisters who are graduates of the Sisters Leadership Development Initiative in Ghana, Uganda and Kenya. Seeing the works that these alumnae are engaged in left me convinced that Catholic sisters are not only changing societal attitudes but also continue to bring renewal to underserved persons. To be sure, the investment made by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, which funds the leadership development initiative, is evident in ministries that are imparting values, building dreams and improving the quality of life for young and old in Africa. (Global Sisters Report is also is funded by the Hilton Foundation.)

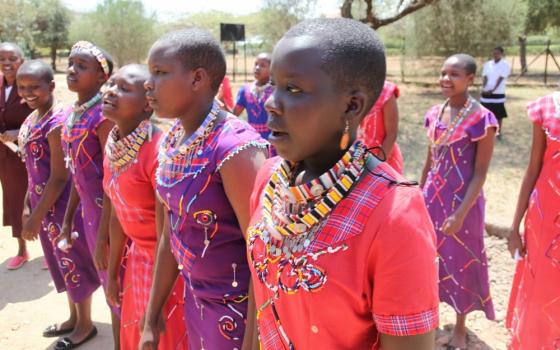

We drove for over two hours on a winding dirt road, a billowing cloud of dust following in our wake. Tired but optimistic, we finally got to our destination, which is located 75 kilometers (46.5 miles) northwest of Nairobi at the Ewaso Kendong parish of the Ngong diocese. Kimani, the director, joined with 15 girls to form a line to welcome us. Their voices were a marvel, and we joined in their dance. Kimani led the way, accompanied by four other sisters.

Nothing about the center appeared unusual until its extraordinary story started to unfold in the speeches that followed. All of the girls had escaped from their homes because their families and community were forcing them to undergo female genital mutilation (FGM); at the Maria Adelaide Center, they have found a new home.

Wild animals are a common occurrence in this underdeveloped region, but that did not deter most of the girls from running away at night to escape this cultural ritual and then being married off.

Although FGM has been outlawed in Kenya since 2001, a public health survey conducted in 2009 revealed that 27 percent of women have been subjected to it. Notable ethnic communities in Kenya continue to practice the ritual, including Somalis (98 percent) and Maasai (73 percent).

The center was established by the Society of the Daughters of the Heart of Mary in 2006 at the request of the local chief. The challenge of rescuing girls was apparent, but there was no safe place to take them.

A donation by the congregation’s European and American provinces allowed for a formal construction of the Maria Adelaide Center in 2009. (Until 2009 the center was a small room; the donation created room to house more girls. The structures are built to mimic the traditional Maasai hut, a symbol of community). The center houses 15 girls. Another 15 are enrolled at various boarding schools in Kenya.

Kimani, a Daughter of the Heart of Mary, moved us to tears describing the extremely courageous experiences of girls who escape from their families at wee hours of the night. One of the girls, whom Kimani called “Mercy” to protect her identity, had escaped after her mother told her that the “cut” ritual would to take place the following day.

“Dogs were barking all night around the center,” Kimani explained. “Early in the morning, Mercy was standing at the corner of the entrance to the center; her face told of her plight.” Mercy, like many other girls, was not ready to undergo the ritual; nor was she prepared to be married off before she had acquired an education.

Before a girl is accepted into the center it is procedure to notify the chief, who then investigates allegations, Kimani explained. Only then can a girl be accepted into the center.

Together with the sisters, Kimani often initiates communication and conversation with a girl’s family to foster reconciliation. A condition is that the girl’s wishes must be respected. Some families have undergone reconciliation, but others find the process, which requires time, to be difficult.

Another girl, who we will call Teresa, explained that she was forced to undergo the ritual and was married off at age 12. Without an understanding of motherhood, Teresa ran away to the center. Now16, Teresa is in school and wants to be a doctor.

Catholic sisters continue to work as a team to change the educational trajectory of girls, shouldering the burden of putting them through school and providing their necessities. Kimani partners with Jamaa Village in Nairobi, a center run by the Sisters of Charity, where she takes pregnant girls who have come to Maria Adelaide. At Jamaa Village, the girls are supported to bring their pregnancies to term and to return to school while sisters take care of their children.

More is needed than just talking about the dangers of FGM, Kimani concluded. To eradicate it, we must invest in the enlightenment and education of the community, particularly in schools, where social and community values are disseminated.

[Sr. Jane Wakahiu is executive director of the African Sisters Education Collaborative and director of the Sisters Leadership Development Initiative.]