For decades, Mexico has been embattled in drug and crime wars that have claimed the lives of countless people. In September, Mexico became a “nation in mourning” after 43 college students went missing – and some are accusing José Luis Abarca, the mayor of the city where the students went missing, and his wife.

This week, Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto is visiting the White House in an attempt, analysts say, to salvage his own scandal-ridden image. But can Mexico itself be saved? Last spring, the University of San Diego’s Justice in Mexico program published a report about drug crime in Mexico.

According to the report:

- Drug-related homicides in Mexico reached a record low in 2007. That year, the homicide rate was 8.1 per every 100,000 people. Homicides peaked four years later – in 2011 – when the homicide rate was 23.7 murders for every 100,000 people.

- Vigilante self-defense groups have become an increasingly common way for civilians to defend themselves against drug lords. However, support for these groups is split. When polled, 43 percent of Mexicans said the groups were a good idea, while 45 percent did not.

- President Peña Nieto was elected, in part, because of his campaign promises to focus less on combating drug trafficking and more on issues threatening civilians – homicide, kidnapping, extortion, etc. In his first year in office, the numbers show that he has, in fact, focused less on trafficking; with 235.5 kg of opium and 3.70 metric tons of cocaine seized, drug seizures under the Peña Nieto administration are lower than they have been under any Mexican president since the ‘80s.

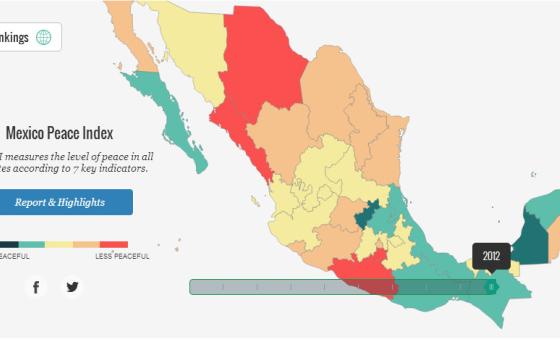

This interactive map from Vision of Humanity, a peace advocacy group, shows the peace index – based on seven key indicators, including justice efficiency and incarceration – for every state in Mexico.